The Remarkable Red Of Viña Vik

I have had the fortune to explore numerous wine regions around the world, but never have I stayed in a hotel quite like Viña Vik. This new property gleams from its hilltop perch like an alien space base, its spiraling titanium roof a beacon above the vineyards. And what vineyards!

They grow in the valley and up the sides of the low mountains surrounding the hotel on all sides, until finally they give way to groves of acacia. A small lake covers much of the rest of the valley floor, where flocks of waterfowl gather. It is a sublime landscape. Every view from the hotel is a vineyard view.

They grow in the valley and up the sides of the low mountains surrounding the hotel on all sides, until finally they give way to groves of acacia. A small lake covers much of the rest of the valley floor, where flocks of waterfowl gather. It is a sublime landscape. Every view from the hotel is a vineyard view.

On the map in my World Atlas of Wine, Viña Vik looks to be just a stone’s throw from one of my favorite Chilean wineries, Casa Lapostolle. But Viña Vik is on the edge of the Cachapoal Valley, and Casa Lapostolle is in the Colchagua Valley. I was disappointed to learn that despite their proximity as the crow flies, it takes well over an hour to drive between them, skirting a high ridge. Fortunately, confining myself to the Viña Vik property didn’t feel like much of a sacrifice.

I toured the vineyards with Miguel, a young gentleman who “used to hate wine.” It seems working at Viña Vik has changed all that — his passion for wine became quite clear as he showed me the 950-some acres of vineyards and led me through a tasting. He pointed out where Cabernet was planted, where Merlot, and the hillsides of slower-ripening Carmenère, Chile’s signature variety. “All the vines are grafted onto American rootstocks,” he explained, “because of the phylloxera.”

Confused, I replied, “But there is no phylloxera in Chile.” Chile is one of the few wine-growing countries in the world as yet unaffected by the destructive aphid-like pests.

“American rootstocks give you better grapes,” he quickly responded. He gestured towards the panorama of grape vines before us. “These are the only vineyards in Chile growing on American rootstocks.”

The quality of American versus European rootstocks is up for debate, but the care with which Viña Vik selected its rootstocks is indisputable. In the strikingly contemporary winery — water flows all around the boulders scattered about its roof, keeping the barrel room cool and humidified — he showed me several maps of the valley. Agronomists had carefully tested the soil composition at regular intervals, and Viña Vik determined which of seven different American rootstocks best matched the soil in each parcel of land. Though a certain section of the valley may be all Cabernet, for example, those vines aren’t necessarily growing on the same type of rootstock.

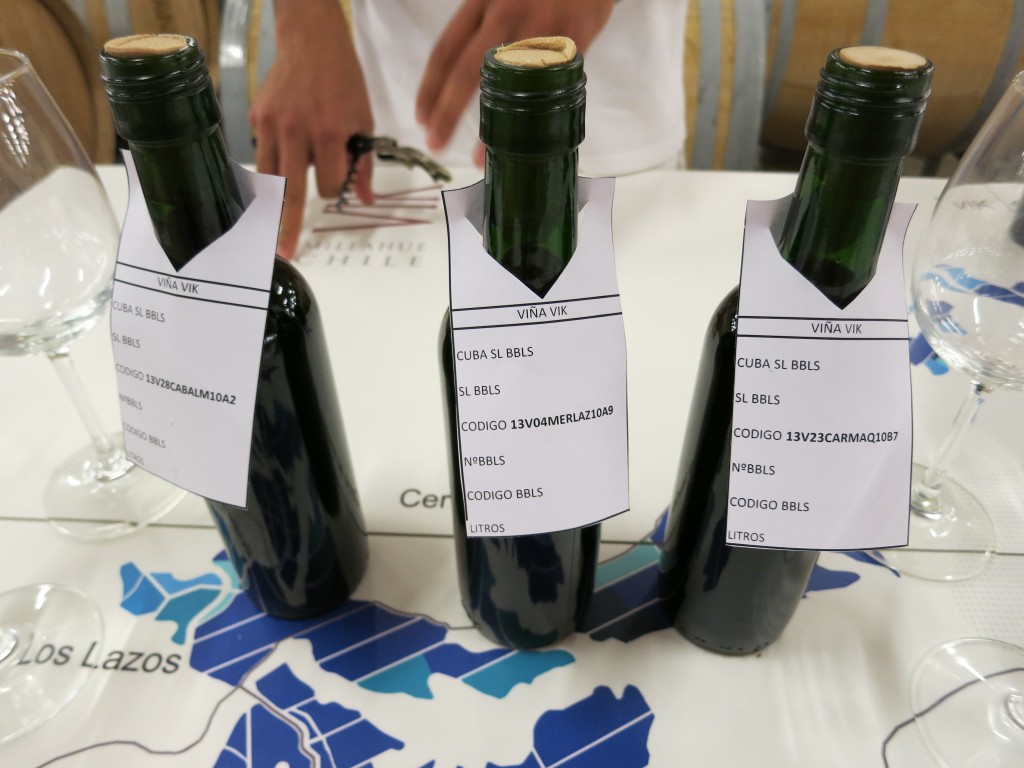

Miguel guided me through an absolutely fascinating private tasting in the barrel room. The winery currently produces only one wine, but Miguel didn’t restrict the tasting to that one red blend. First, we tried some of its component parts, including a big, tough and well-structured 2013 Cabernet Sauvignon; a round, decadent and much softer 2013 Merlot; and a complex and earthy 2013 Carmenère with a finish redolent of mesquite smoke and spice. (Syrah also goes into the mix.)

Miguel guided me through an absolutely fascinating private tasting in the barrel room. The winery currently produces only one wine, but Miguel didn’t restrict the tasting to that one red blend. First, we tried some of its component parts, including a big, tough and well-structured 2013 Cabernet Sauvignon; a round, decadent and much softer 2013 Merlot; and a complex and earthy 2013 Carmenère with a finish redolent of mesquite smoke and spice. (Syrah also goes into the mix.)

Tasting these components helped me identify their contributions to the final blend. The 2010 Vik had an enticing aroma of dark, almost jammy fruit mixed with some meatiness and some vanilla. It had notable structure, with dark fruit and big spice, which changed from green peppercorn to red paprika. Something fresh underneath kept the wine from being heavy, and the tannins were big enough to make me want to lay the bottle down for another couple of years. The finish went on and on.

I found this wine for sale here in the U.S., retailing for $150 at Sotheby’s Wine. Yet the Viña Vik hotel pours the wine freely as its house red! Each lunch and dinner, decanters of the stuff would appear, and waitstaff would fill our glasses as often as we liked. It was always served too warm, alas, but even so — what a treat! It worked especially well with a dish of Wagyu beef slow-cooked for 24 hours and served with a rich potato purée.

I’ll never forget my stay at Viña Vik. Because of the wine, yes, but also because of the 4.8-magnitude earthquake which startled this Midwesterner out of bed one morning. It lasted all of six or seven seconds, but that was enough to have me springing out of the sheets and diving, naked, under the desk.

And there was the afternoon an odd smoggy haze filled the valley and drifted over the hotel. I later learned that it was no smog. At dinner, a couple related how they had been hiking and encountered a helicopter manned by heavily armed guards. Instead of walking the other direction, they approached and asked for the time. The guards, it turned out, were the Chilean equivalent of DEA agents. They had discovered an illegal field of marijuana on public land adjacent to the hotel’s property and were setting it on fire. That was the smoggy haze — a great cloud of pot smoke! No wonder the Wagyu beef tasted so good that night…

And there was the afternoon an odd smoggy haze filled the valley and drifted over the hotel. I later learned that it was no smog. At dinner, a couple related how they had been hiking and encountered a helicopter manned by heavily armed guards. Instead of walking the other direction, they approached and asked for the time. The guards, it turned out, were the Chilean equivalent of DEA agents. They had discovered an illegal field of marijuana on public land adjacent to the hotel’s property and were setting it on fire. That was the smoggy haze — a great cloud of pot smoke! No wonder the Wagyu beef tasted so good that night…