Prosecco: The Good Stuff

How many parties have I attended at which I spotted a bottle of cheap Prosecco, perhaps even served in a red plastic cup? Frankly, it’s usually a relief — I’d much rather sip a $10 Prosecco than a Barefoot Bubbly or some such. Even inexpensive Prosecco is usually cheerful and well-balanced, if not anything worth deep contemplation. Really, though, what more can one ask from a party wine?

But cheap and cheerful is not Prosecco’s only mood, as reaffirmed by a recent lunch I attended that was hosted by the Consorzio Tutela del Vino Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco. (Full disclosure: The lunch and wines were provided free of charge.) We tried seven different Proseccos, all of which exhibited complexity as well as food-friendliness. The trick is that these were all classified as Prosecco Superiore DOCG.

Most Proseccos, and certainly the most inexpensive ones, are classed as DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata). These wines come from grapes grown anywhere within the DOC zone — Italy’s largest DOC, in fact — an expanse of almost 35,000 acres. Most of this DOC is flat and relatively unexciting, at least in vinous terms.

The vineyards with more potential for high quality are in the smaller DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) zone. The approximately 15,000 acres of the Prosecco DOCG occupy picturesque hills around the towns of Conegliano and Valdobbiadene, hence the consorzio’s rather unwieldy name. Fortunately for the non-Italian-speaking consumer, there is no need to remember the name of the consorzio or the towns. If you look for Prosecco with the letters DOCG on the label, you’re off to a good start.

Meyer lemon semifreddo with fresh berries and cardamom granola at Sepia

Terroir geeks will want to go one step further and look for the word “Rive,” which indicates that the grapes for the Prosecco were grown on an especially notable site. We tried two such Proseccos at the lunch. The 2018 Sommariva Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Rive di S. Michele Extra Dry had an enticing orangey aroma, sharp and frothy bubbles, and notes of sweet chalk and dark citrus. It was an excellent pairing with some salmon topped with preserved lemon-caper butter. And the 2018 Adami Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Vigneto Giardino Asciutto Rive di Colbertaldo — good gracious, just writing out the names of these wines doubles the word count of this article — felt ripe and lush but pointy, with juicy acids and elegantly sharp bubbles. It was just sweet enough to pair with some Meyer lemon semifreddo.

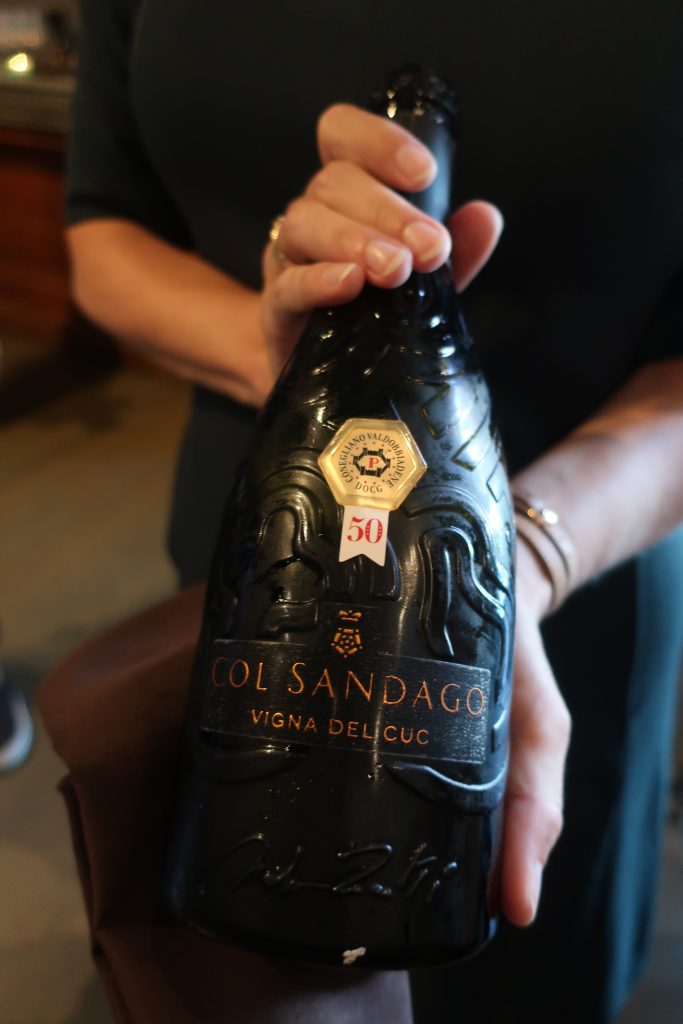

The drier Proseccos we tried were also delicious (“extra dry” is, confusingly, not as dry as “dry” or “brut”). There was the ethereal NV Bisol Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Jeio Brut, which had notes of melon and citrus; its round, full mouthfeel evaporated into prickly froth. The NV Villa Sandi Valdobbiadene Superiore di Cartizze Brut La Riveta smelled of chalk, lime and stone fruit, and though its acids and bubbles were zesty, it felt classy, finishing on a mineral note (the word “Cartizze” on a label is also encouraging; the vineyards there are particularly well-regarded). I also enjoyed the well-balanced and elegant 2018 Col Sandago Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Vigna del Cuc Brut, which we sipped as an aperitif.

Only the 2017 BiancaVigna Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Rive di Soligo Dossagio Zero was not to my taste. This bottle had lots of promising words on its label — Superiore, Rive, DOCG — but two of those words were deal-breakers for me: Dossagio Zero. The equivalent of “Zero Dosage” or “Brut Nature,” Dossagio Zero means, essentially, that the wine is bone-dry (see here for a more in-depth explanation). I like dry wine, up to a point. But sugar in wine can be like salt in food. You need a little bit sometimes, for balance. This wine tasted bracingly tart on its own and was palatable only when paired with food. There surely are some good sparkling wines that are Dossagio Zero, Zero Dosage or Brut Nature, but I have tasted precious few of them.

Only the 2017 BiancaVigna Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Rive di Soligo Dossagio Zero was not to my taste. This bottle had lots of promising words on its label — Superiore, Rive, DOCG — but two of those words were deal-breakers for me: Dossagio Zero. The equivalent of “Zero Dosage” or “Brut Nature,” Dossagio Zero means, essentially, that the wine is bone-dry (see here for a more in-depth explanation). I like dry wine, up to a point. But sugar in wine can be like salt in food. You need a little bit sometimes, for balance. This wine tasted bracingly tart on its own and was palatable only when paired with food. There surely are some good sparkling wines that are Dossagio Zero, Zero Dosage or Brut Nature, but I have tasted precious few of them.

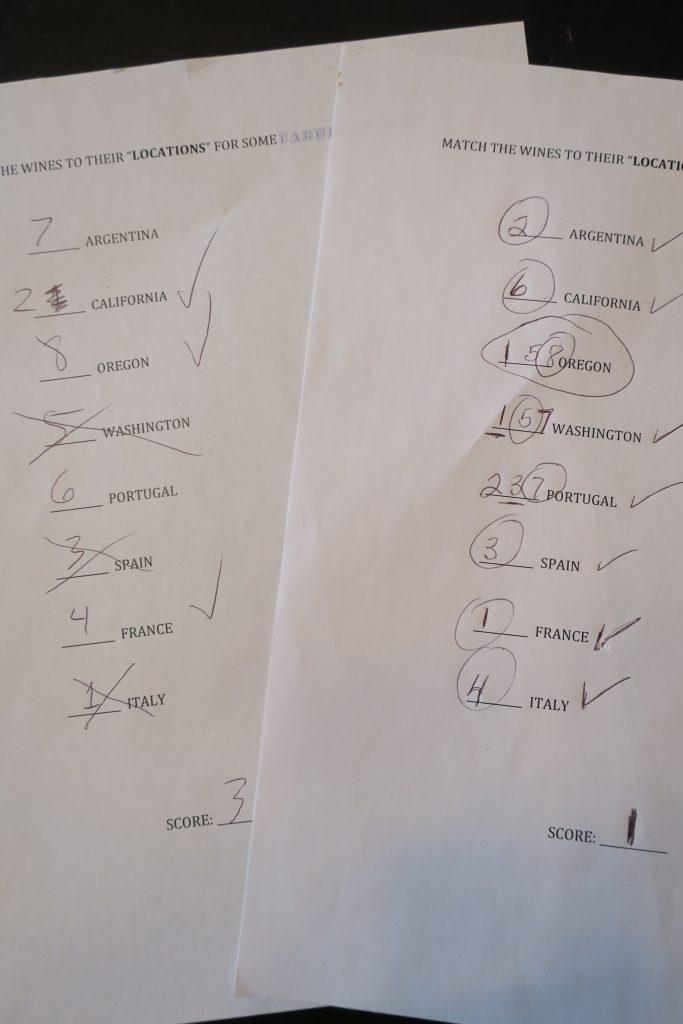

Prosecco Superiore DOCG costs more than Prosecco DOC, of course, and some of you may well be wondering if it’s really worth the extra money. If the descriptions above don’t convince you, consider watching the video below, in which we blind-taste a Mionetto Prosecco DOC against a Mionetto Prosecco Superiore DOCG. They cost about $10 and $20, respectively, which means that the difference between them ought to be readily apparent. We put that hypothesis to the test:

Note: The lunch and Proseccos described in the post above were provided free of charge. The wines in the video we purchased at full retail price.