Soulful Wines From The Heart Of Turkey

When we visited Turkey in 2005, I purchased two bottles of focused and minerally Narince from Cappadocia to bring home. I’ll never forget the expression on our Istanbul guide’s face when I explained how I planned on doing so. “I’ve never had a bottle break in my luggage,” I proudly told her. “To protect them, I stick each bottle inside three or four of my socks.” She looked absolutely horrified. I had forgotten that in Turkey, as in many Muslim-majority countries, many people consider the feet to be unclean.

In spite of my socks, the Narince was thoroughly delicious. It may surprise some Americans that Turkey produces wine at all, let alone wine of high quality. But Turkey has a tradition of winemaking dating back thousands of years, and may in fact be where wine itself originated. Already in 1650 B.C., laws regulated wine production in what is now Turkey. The Oxford Companion to Wine explains:

“Between 1650 and 1200 B.C., when the Hittites ruled most of Anatolia, there were enhanced laws safeguarding viticultural practices and trade routes… Hittites used the word wiyana for wine, influencing the words used in many modern languages.”

Nowadays, unfortunately, the laws work against winemakers in Turkey. Times have changed dramatically since the Hittites, and even since the 1920s, when the resolutely secular Kemal Atatürk openly encouraged winemaking and consumption, “thereby ensuring the survival of indigenous Anatolian grape varieties, which may yet yield clues to the origins of viticulture itself,” according to The World Atlas of Wine. The problems are twofold.

First, there is an absence of law organizing Turkish wine. Yields, grape varieties and vineyard sites are more or less unregulated, which means “the wine scene in Turkey is based on the practice of individual producers,” according to the Oxford Companion.

First, there is an absence of law organizing Turkish wine. Yields, grape varieties and vineyard sites are more or less unregulated, which means “the wine scene in Turkey is based on the practice of individual producers,” according to the Oxford Companion.

Second, the current regime, which does not prioritize carrying on the secular policies established by Atatürk, has enacted numerous laws detrimental to the business of local winemakers. New laws forbid the direct sale of wine over the internet, making it hard for small wineries in particular to grow their sales. Advertising — including the sponsoring of festivals or public promotions of any kind — is forbidden. Bottles must carry labels warning against the dangers of alcohol. And retail sales between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. are also forbidden.

Making wine is not easy pursuit in any country, but in Turkey, laws like these make it especially difficult. A winemaker dedicated to producing high-quality wines must have true passion to succeed. That passion, combined with Turkey’s unique and ancient indigenous grape varieties, results in some very exciting wines indeed.

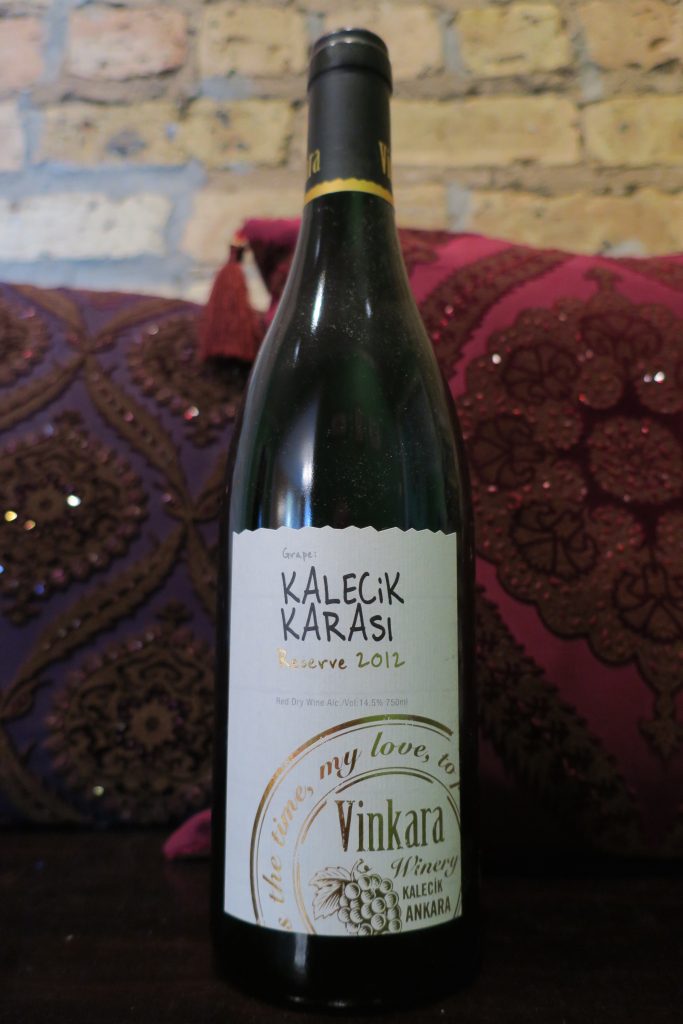

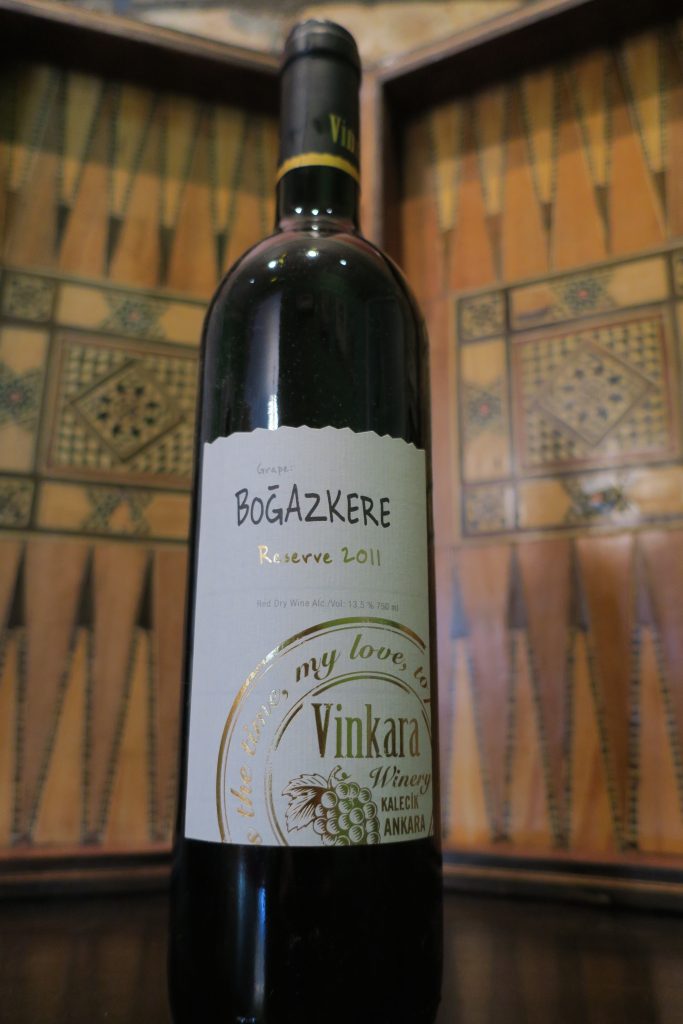

Some of the most exciting are made by a winery called Vinkara, located near Turkey’s capital, Ankara. This is the home of Kalecik Karasi, a “native black grape variety… saved from extinction during the 1970s,” according to the Oxford Companion. A PR firm sent me a bottle of it, along with a bottle of Boğazkere, a thicker-skinned grape indigenous to southeastern Anatolia, which also grows well near Ankara.

These two wines are among the most soulful I’ve tasted in some time.

The 2012 Vinkara Kalecik Karasi Reserve, aged 14 months in 225-liter oak casks, came in a Burgundy-style bottle. It had a dark fruit aroma, like prunes, with an undertone of spice. The flavor was rich, rich, rich, and the wine felt almost chewy with ripe dark fruit. It moved on to baking spice and supple tannins, and I noticed a hearty, meaty undertone. With some beef lagman (I tried this wine over some Kyrgyz food at Jibek Jolu, a BYOB restaurant near me in Chicago), an additional vanilla note revealed itself.

The 2012 Vinkara Kalecik Karasi Reserve, aged 14 months in 225-liter oak casks, came in a Burgundy-style bottle. It had a dark fruit aroma, like prunes, with an undertone of spice. The flavor was rich, rich, rich, and the wine felt almost chewy with ripe dark fruit. It moved on to baking spice and supple tannins, and I noticed a hearty, meaty undertone. With some beef lagman (I tried this wine over some Kyrgyz food at Jibek Jolu, a BYOB restaurant near me in Chicago), an additional vanilla note revealed itself.

A Bordeaux-style bottle contained the 2011 Vinkara Boğazkere Reserve, and indeed, if the Kalecik Karasi could be compared to Pinot Noir, the Boğazkere was more like Cabernet Sauvignon. Aged 30 months in 225-liter oak casks, it had a dusty dark fruit aroma with a savory undertone, and it tasted of richly ripe dark fruit as well. After the fruit, a pop of acids grabbed my attention, which resolved into hefty but well-integrated tannins followed by a white pepper finish. The wine became more peppery with the lagman as well as some beef manti dumplings.

Moved by the depth of these wines, I sent some questions to Ardiç Gürsel, who founded the winery with her family in 2003.

–How were you first introduced to fine wine, and what made you decide to start a winery?

“I became interested in wine some time ago, while in college, naturally enough. I started to wonder why, with such a rich and varied heritage, is Turkish wine not more popular. As time went on I began by looking into grape production in Turkey. I needed to understand whether it was possible to produce world-class wine using indigenous Turkish grapes. We researched the grapes, the climate, the terrain, the chemical composition of the soil and many other variables. Everything we found out was telling me one thing: Yes! I could do this.”

–I read that wine consumption in Turkey averages only one liter per person per year. Are you able to sell much of your wine in Turkey? Or do you export most of your wine?

“Correct! Not a lot of Turkish people drink wine. Most of the wines are consumed by the foreign visitors. At the height in 2014, Turkey attracted around 42 million foreign tourists. This number, however, declined to 36 million in 2015 and deteriorated further in 2016, due to political tension and terrorist attacks. The adverse performance of the Turkish travel and tourism industry, bans on the advertisement and promotion of all alcoholic drinks, and rising excise taxes have restricted the volume of wine sales within the country.

“Today we export 20,000 liters of our wine production, and we plan to increase our sales abroad up to 120,000 within the next five years.”

–My 2013 edition of The World Atlas of Wine tells me that “younger and more cosmopolitan Turks are beginning to take an interest in wine.” Has that trend continued? Or has it reversed in recent years?

“There is a great interest in wine among cosmopolitan Turks. The trend is still on.”

–When you work with foreign wine consumers, do you find that they have a lot of misconceptions about Turkish wine?

“Turkish winemaking began to evolve only in 1990s. In the early 2000s, 15 to 20 new wineries were established. Fine wines and wine styles from different wine regions were introduced by the late 2000s to international markets. There is very little knowledge by the foreign consumers. In fact, they are very surprised that wines are produced in a Muslim country.”

–I see you also make a Narince in addition to the Kalecik Karasi and the Boğazkere. Do you plan on adding any additional grape varieties to your winemaking portfolio in the coming years?

“So it was and remains as my mission to offer something unique to our customers. As long as we find a worthwhile local grape, we definitely would invest on the grape. Hasan Dede, a white variety indigenous to the Kazmaca area in Anatolia, is the latest one we included to our range.”

–Is there anything else you’d like to tell me about your wine?

“At Vinkara, we have successfully reintroduced grapes indigenous to Turkey, to offer full-bodied wines that are not only of the highest quality, but that are intense and abundant of flavour, and that offer our customers something truly exceptional: a new experience that is faithful to the origins of wine. I’m extremely proud of where we are today. I love what we do, and I love our wine. I sincerely believe we’re at the forefront of world-class wine production within the emerging markets, and this has been reinforced by the many great reviews we’ve been fortunate enough to receive.”

Ardiç Gürsel

How ironic that Turkey, likely the place where wine originated, now finds itself as an emerging producer of world-class wine. Turkey is most certainly that, thanks to the efforts of passionate producers like Ardiç Gürsel, who perseveres in spite of the legal roadblocks placed in her way.

Turkish wine is an important part of the heritage of all of humanity, a fact which Turkey’s current government chooses to ignore. It was here that one of the world’s most cherished beverages had its beginnings, and yet, in wine’s very birthplace, misguided laws threaten its existence.

Gürsel and her fellow winemakers produce world-class wines in a deeply historic but increasingly tough neighborhood. They need our support. But don’t buy Vinkara’s wines out of a sense of altruism. Buy Vinkara’s wines because they have palpable depth and soul, and a lineage reaching back to the dawn of civilization.

Note: The two bottles of Vinkara wine were provided to me as tasting samples free of charge.