Book Review: Alice Feiring’s For The Love Of Wine

Image courtesy of Amazon

I felt sad when I finished reading “For the Love of Wine: My Odyssey Through the World’s Most Ancient Wine Culture.” Sad and frustrated. I’d purchased the book to help me prepare for my trip to the Republic of Georgia last year. Published in 2016, it’s on many people’s suggested reading lists, and it’s still the first search result if you Google “Georgian wine book.” For the moment, “For the Love of Wine” seems to be the most important English-language book about the wines of Georgia.

When I read a wine-travelogue, I want two things. First, I want lots of good information about a place’s wine, culture and history, related in a readable way. Second, I want to wish that I had been traveling along with the writer, living vicariously through her experiences. “For the Love of Wine” provides the first, certainly, and most certainly not the second.

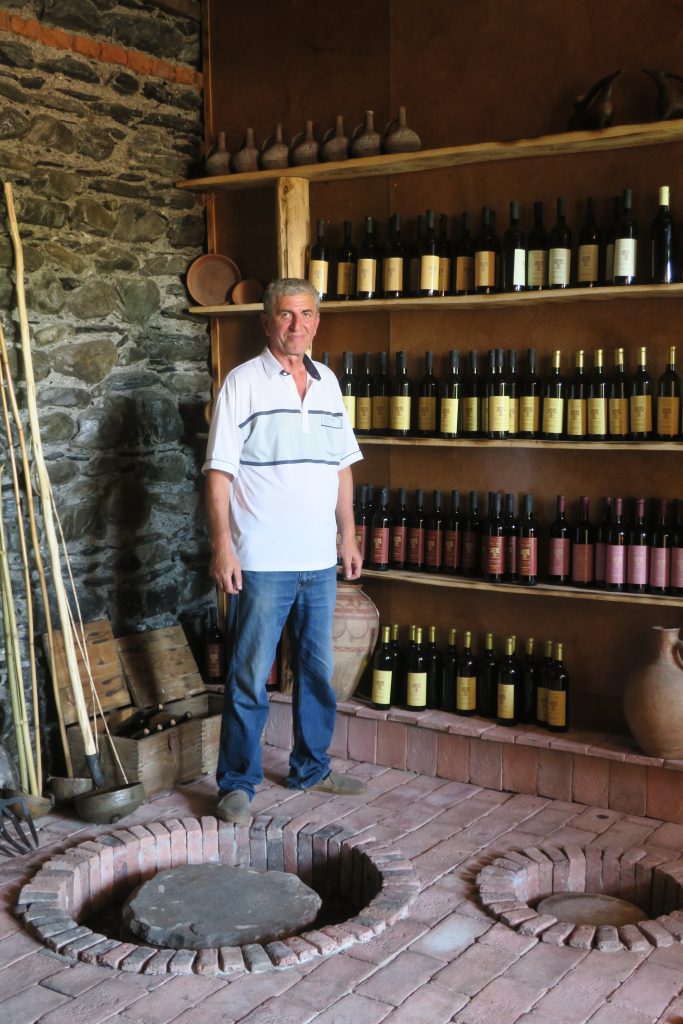

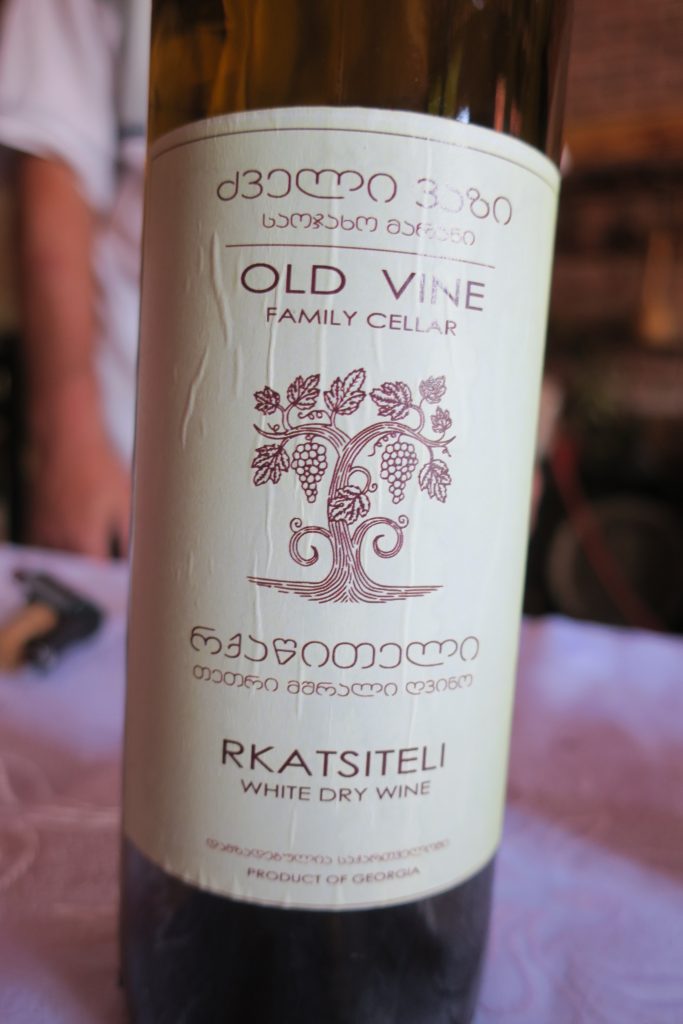

I agree with much of what she wrote about Georgian wine, and wine in general. The country’s wine is special, made from an array of unique indigenous grapes vinified using techniques that can be traced with startling directness back to the Neolithic era. Clay vessels that held wine some 8,000 years ago bear a striking resemblance to traditional Georgian qvevri, amphorae-like containers used to ferment wine to this day. And it really would be a shame if that heritage were to be cast aside in favor of more standard winegrowing and winemaking techniques.

What’s sad is that I found myself wanting to disagree with Feiring at every turn, because she has such a moralizing and combative tone. I very much enjoy the natural wines of Georgia as well as those from other countries, and there’s a case to be made that natural wines — made organically and with minimal intervention in the winery — deserve more attention and support. But for Feiring, natural wine is good and conventional wine is bad, full stop. The (conventional) wines of France are “weak,” for example, but the natural wines of Georgia are strong, wild, complex and full of emotion. I don’t trust a wine writer who dismisses 98-99% of the wines on the market (estimates suggest natural wines represent 2% or less of wines on the shelves).

Her uncompromising views unfortunately spill out into her interpersonal relations, and her descriptions of the interactions were painful for me to read. One young man she meets, for example, expresses a desire to make conventional wines. She proceeds to shame him:

“You just want it cushy,” I chided him, and he good-naturedly laughed. “You can get a job with a big factory, but would you be able to sleep well at night knowing you were making wine you didn’t really want to drink? Wouldn’t you rather make wine like Kakha’s?”

He may have laughed good-naturedly, but I suspect he didn’t enjoy the conversation. Feiring claims to be an old lefty, yet she doesn’t seem to grasp how unpleasant poverty can be. She describes herself as “a writer with poverty always at the door,” but she has an apartment in Manhattan. It hardly seems fair to expect this young Georgian gentleman to follow a traditional agrarian life if he prefers to do otherwise, in order that Feiring can get the kind of wine she prefers to drink while living in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

Unfairness becomes hypocrisy when a winemaker complains that he has trouble finding people willing to clean his qvevris. Feiring, who criticizes Georgia’s young winemakers more than once for wanting it “cushy,” does not put her money where her mouth is and volunteer to help. Instead, she nominates her traveling companion: “‘Here he is; here’s your guy,’ I said, offering up Jeremy for the task.” It’s difficult to empathize with Feiring’s judgmental attitude towards those unwilling to clean qvevri when she never does the dirty work herself.

Feiring shames other Georgians over the course of her travels as well. In this example, she shames a winemaker for not giving his wife some qvevri in which to make her own wine:

“And where’s Marina’s qvevri?” I asked, eager to see the continuation of his wife Marina’s wine. Iago looked hangdog. “But why!” I gasped. It seemed incomprehensible. The wine was so very good. It was so important for women to be seen in the wine world, as it can in truth get to be too much of a boys’ club. “There was no room; I needed all the qvevris this year,” Iago explained. “Marina and Téa didn’t get their qvevri?” I repeated. I mean, how could he? The doting husband Iago? How could he not take care of his wife? I was crushed. He looked crestfallen.

Of course he looked crestfallen. In this situation, Feiring exhibited no empathy towards Iago. All that mattered were her own feelings about the subject. Feiring admits in the book that her emotions are “too raw and intense for [her] own good.” She writes how she often feels “…too emotional to live in the real world, but in Georgia everyone seemed like a mythical human who felt first and thought later. [She] felt at home.”

But the problem is not emotions that are too intense. Everyone has feelings, often strong ones. The trick is to express one’s feelings, however strong they may be, in a non-shaming, non-judgmental way. It’s not easy for most of us, but it’s possible, and it’s necessary.

I’m calling out Feiring’s behavior because she, like all travelers, is an ambassador. I want representatives of America, and more specifically of American wine writers, to represent their constituencies well. It helps future travelers. On the other side of the coin, I also want the wonderful wines of Georgia to have the ambassador that they deserve.

Image courtesy of Amazon

In addition, I want wine and travel writing that is clear and well-crafted. When Feiring writes, “Soon he would add a veritable tasting room as well,” does she mean that it’s a true tasting room? Or not quite a real tasting room? I also felt confused when Feiring “took a cup of nubile juice from him” and when she described “hunting down nubile, home winemaking talent.” Was the juice sexually attractive? Is sexiness what they’re really looking for in a winemaker? But Feiring left absolutely no doubt about a certain local baked good: “There was bagel-like bread that immediately made me think of bagels…” Got it. Bagel.

Finally, Feiring’s economic analysis leaves something to be desired. She writes, “It was then that everything crystallized for me: communism under the Russians and modern-day capitalism were twins separated at birth. Neither fostered or celebrated the individual.” It escapes her notice that the free market, specifically the market’s demand for the supply of Georgia’s unique wines, is precisely what has allowed there to be a renaissance of traditional Georgian winemaking. As a utopian ideology, communism allows only its ideal: proletariat-run factories making wine for the proletariat. Capitalism is non-utopian, which means the system has room for factories and small family-run wineries alike. Communism destroyed the Georgian economy and its wine industry, impoverishing the nation and prioritizing wine quantity over quality. Capitalism has started to bring wealth back to Georgia, and it has thus far encouraged individual winemakers to excel.

It’s so frustrating to read Feiring’s book, because so much of it is fascinating and heartfelt. She relates some incredible experiences, and her love for Georgian wine and culture is palpable. It should be an inspiring work, a paean to the joys of natural wine and feasting with friends and family. But “For the Love of Wine” left a bad taste in my mouth.

If you’re looking for a book about Georgian food and wine — and I highly recommend looking for a book about Georgian food and wine — consider instead Carla Capalbo’s lavishly photographed “Tasting Georgia: A Food and Wine Journey in the Caucasus.” It’s more of a cookbook with additional essays, whereas “For the Love of Wine” is more of a wine/travel book with additional recipes. Even so, it contains excellent, concise information about Georgian wine and cuisine.