The Best Wine Pairing For Thai Food

Every now and then I worry: Is this blog just a really, really elaborate cover for alcoholism? But then I glance at my wine rack, heaving with unopened sample bottles, and I realize that if I were an alcoholic, I would probably have transformed those samples into tasting notes and hangovers long ago. I feel relief, but only for a moment, because it strikes me that the wonderful PR people who sent me those dust-gathering samples would probably rather that I were an alcoholic.

Every now and then I worry: Is this blog just a really, really elaborate cover for alcoholism? But then I glance at my wine rack, heaving with unopened sample bottles, and I realize that if I were an alcoholic, I would probably have transformed those samples into tasting notes and hangovers long ago. I feel relief, but only for a moment, because it strikes me that the wonderful PR people who sent me those dust-gathering samples would probably rather that I were an alcoholic.

In an effort to catch up, I brought two of my sample shelf’s oldest residents to Andy’s Thai Kitchen, a BYOB restaurant near the home of one of my favorite wine tasting friends, Liz Barrett, the Vice President of Corporate Communications and PR at Terlato Wines, one of Chicago’s most important wine importers and distributors. The company recently made news for severing its relationship with Santa Margherita, of Pinot Grigio infamy, and good riddance, too. (Terlato’s Friuli Pinot Grigio is ever so much better. It has important qualities lacking in the Santa Margherita, such as flavor.)

As Liz and I unloaded our wine onto our too-small table — five bottles in all — I briefly reconsidered my potential alcoholism, but that unpleasant thought was swiftly washed away by the exquisite Riesling Liz poured into my glass. Riesling and Gewürztraminer are classic choices for pairing with Thai food, and she brought along beautiful examples of each.

As Liz and I unloaded our wine onto our too-small table — five bottles in all — I briefly reconsidered my potential alcoholism, but that unpleasant thought was swiftly washed away by the exquisite Riesling Liz poured into my glass. Riesling and Gewürztraminer are classic choices for pairing with Thai food, and she brought along beautiful examples of each.

Both came from the Alsace, a region in eastern France along the border with Germany, which excels at producing dry whites (most famously, as luck would have it, Riesling and Gewürztraminer). Wines from the Alsace rarely lack acidity, and they sometimes even verge on the austere, making them an excellent choice if sweetness in wine gives you the heebie-jeebies.

The wines were created by Michel Chapoutier, a family wine company distinguished, according to The Oxford Companion to Wine, by “its combination of high quality, often vineyard designated, and almost restless vineyard acquisition.” Chapoutier released his first Alsatian vintage in 2011, from fruit grown “on the only vein of blue schist in the Alsace region,” according to the Schieferkopf website. “Schieferkopf” literally means “head of schist.”

The 2012 Schieferkopf “Via Saint-Jacques” Riesling lived up to its hefty price tag of about $45, with a rich attack, wonderfully juicy and focused lemon/orange acids and a surprisingly long and minerally finish. “It’s crisp and rich at the same time,” Liz noted. Absolutely. It paired beautifully with some sweet and salty chicken satay — it even cut through the heavy peanut sauce — and the wine positively sang with some savory gyoza dumplings. (Why so many Thai restaurants insist on also serving Japanese food is beyond my comprehension, but at least Andy’s didn’t attempt sushi.)

The 2014 Schieferkopf Gewürztraminer — which had a seductive nose of honeysuckle and perfectly balanced flavors of tropical fruits, taut orangey acids and exotic spice — fell rather flat with the gyoza and satay, however. It felt tamped down. But paired with an aromatic and slightly spicy dish of fermented Isaan sausage with cabbage, fresh ginger and peanuts, the wine became magnificently bright and lively. It also stood up well to some sweet and spicy pork belly as well as some slightly spicy shrimp pad Thai.

The 2014 Schieferkopf Gewürztraminer — which had a seductive nose of honeysuckle and perfectly balanced flavors of tropical fruits, taut orangey acids and exotic spice — fell rather flat with the gyoza and satay, however. It felt tamped down. But paired with an aromatic and slightly spicy dish of fermented Isaan sausage with cabbage, fresh ginger and peanuts, the wine became magnificently bright and lively. It also stood up well to some sweet and spicy pork belly as well as some slightly spicy shrimp pad Thai.

I wouldn’t be Odd Bacchus if I stuck to classic pairings, of course, and so I selected some less conventional (and less expensive) wines to sip with our Thai/Japanese feast.

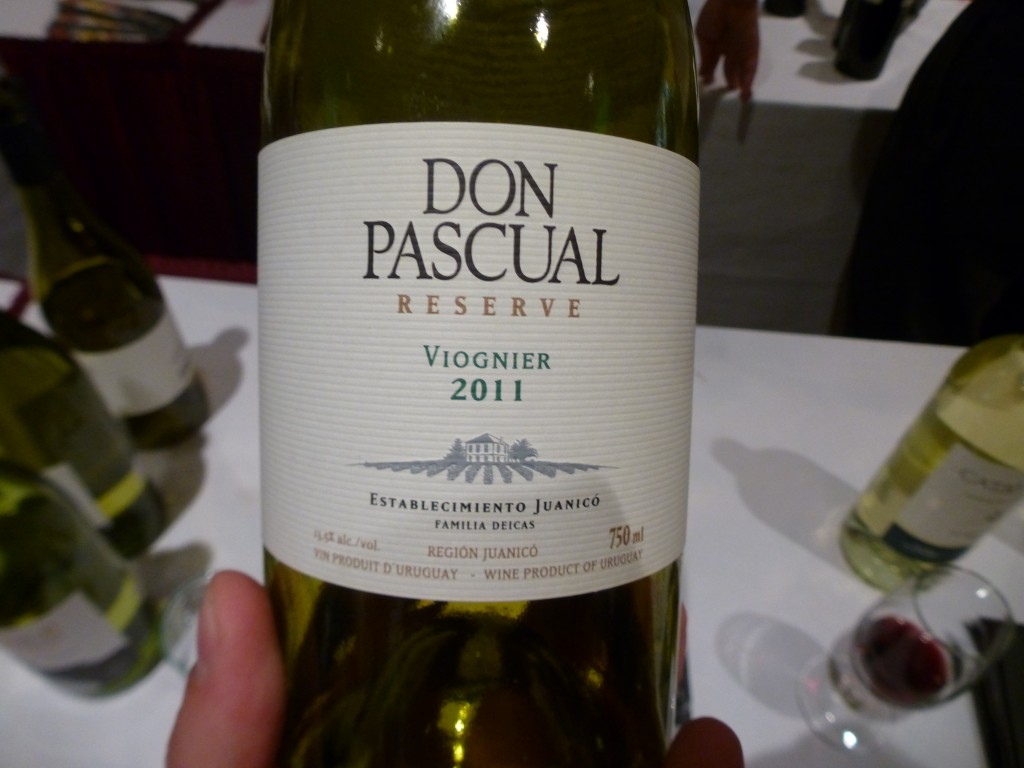

Remembering how much I loved the 2010 Planeta Carricante, with its lush fruit and incense-like spice, I brought along a bottle of 2014 Alta Mora Etna Bianco, made from 100% Carricante, an ancient grape variety grown on the slopes of Mount Etna. Etna wines have become rather fashionable these days, and when you sip wines like the Planeta and the Alta Mora, it’s easy to see why. Again, I noted something exotic and “incensy” in the nose, and the wine had some real heft on the palate. Nevertheless, it felt taut and dry, with some tart acids and an impressively long finish.

The Alta Mora worked well with the gyoza (though not as beautifully as the Riesling), and even better with the Isaan sausage. It became more integrated with the food, pairing well with just about everything on the table. But it was two days later when this wine most impressed me. I had taken the mostly full bottle home with me and stored it in the fridge. I thought that after two days, it would be barely drinkable at best, but it still tasted mostly intact. I suspect this wine could age well for a number of years. A fine value for about $20 a bottle.

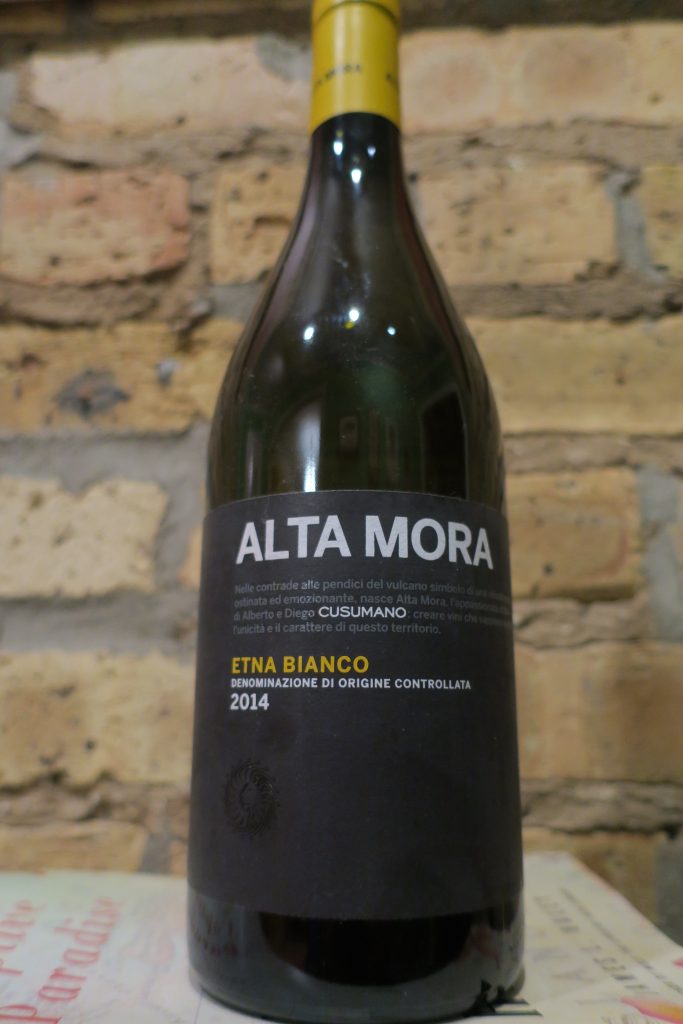

The 2015 Ernie Els “Big Easy” Chenin Blanc from South Africa also paired generally well with all the food on the table. It tasted very citrusy, with broad, orangey acids, and it had a spicy gingery finish. The wine retained its acids and spice when matched with the satay and peanut sauce, and with the Isaan sausage it became even bigger and spicier. “This is just the right Chenin for this food,” Liz remarked, and I agreed. I wouldn’t hesitate to spend $15 of my own money on a bottle.

The 2015 Ernie Els “Big Easy” Chenin Blanc from South Africa also paired generally well with all the food on the table. It tasted very citrusy, with broad, orangey acids, and it had a spicy gingery finish. The wine retained its acids and spice when matched with the satay and peanut sauce, and with the Isaan sausage it became even bigger and spicier. “This is just the right Chenin for this food,” Liz remarked, and I agreed. I wouldn’t hesitate to spend $15 of my own money on a bottle.

If you’re a red wine lover, I hope you haven’t given up on this post just yet. I also brought along a 2013 Nadler “Rote Rieden” Zweigelt from Carnuntum, in far eastern Austria. Austria made its name in the United States with Grüner Veltliner and to a lesser extent Riesling, but it also produces reds of notable character, including Zweigelt. (See my posts about velvety Austrian St. Laurent here.)

This Zweigelt had a light body — ideal for pairing with this sort of food — but no shortage of flavor: cherry, earth, mocha, black pepper… Liz also detected “something herbal, like eucalyptus.” It worked especially well with the pork, which turned the wine’s fruit darker and amped up the black pepper note. Not too shabby for a $13 bottle of wine!

So what do you pair with your favorite Thai treats? That depends. If you plan on ordering some spicy dishes, and you don’t abhor somewhat floral whites, go for a Gewürztraminer. A dry Riesling would be best if you plan on ordering dishes that are more savory than spicy. A light-bodied red like the Zweigelt would be ideal for meaty dishes, both savory and spicy. And if you like a variety of different Thai foods, an Etna Bianco or a Chenin Blanc should work well with a range of dishes.

When in doubt, choose two different bottles. Or better yet, five. After all, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re an alcoholic.

Note: These wines, with the exception of the Nadler Zweigelt, were samples provided free of charge.