Last-Minute Winery Lunch In Kvareli

I felt irritated with my guide, NaNa. We had just spent half an hour driving in circles trying to find the second-prettiest lake in Kakheti, Georgia’s most important wine region (the prettiest lake she wanted to save for later). She was now on her phone, trying to arrange a last-minute lunch at a family winery nearby. When she announced, with palpable relief, that the family could indeed host us, in spite of the short notice, my irritation turned to pleasant surprise, as it so often did in Georgia.

Georgia is not just a state, of course, but a magnificently beautiful country, bordered by the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountains, south of Russia and northeast of Turkey. Winemaking there dates back at least 8,000 years, according to the most recent archaeological evidence, making Georgia the likely birthplace of wine itself. But there were a few viticultural bumps in the road between then and now, most recently the communist prioritization of quantity over quality when Georgia was a part of the Soviet Union.

All my research materials tell me that quality winemaking took off in Georgia only after the Russians banned the import of Georgian wine between 2006-2013, in order to punish the country (recall the brief war in 2008 over Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two regions Russia still illegally occupies). Ironically, according to The Oxford Companion to Wine, “The embargo forced exporters to improve quality and look further afield to more demanding markets such as western Europe, the U.S., Japan, China and Hong Kong.”

Because this development is so recent and ongoing, most books describing Georgian wines are in some respects out of date. The World Atlas of Wine, for example, speaks of Georgia’s “extraordinary potential,” and Uncorking the Caucasus warns that “Obtaining high-quality wine is difficult outside of the niche bars and shops in Tbilisi,” and that even “…in Georgia’s most famous wine region, Kakheti, options were remarkably thin and the wineries were mostly inconveniently spread out over long distances in the valley.”

I visited in June of this year, and nowadays, Georgia is less a country of potential and more a country of results. I found excellent and inexpensive wines all over the place, and in scenic Kakheti, I had no trouble weaving seven winery visits in with my monastery tours and hearty country lunches.

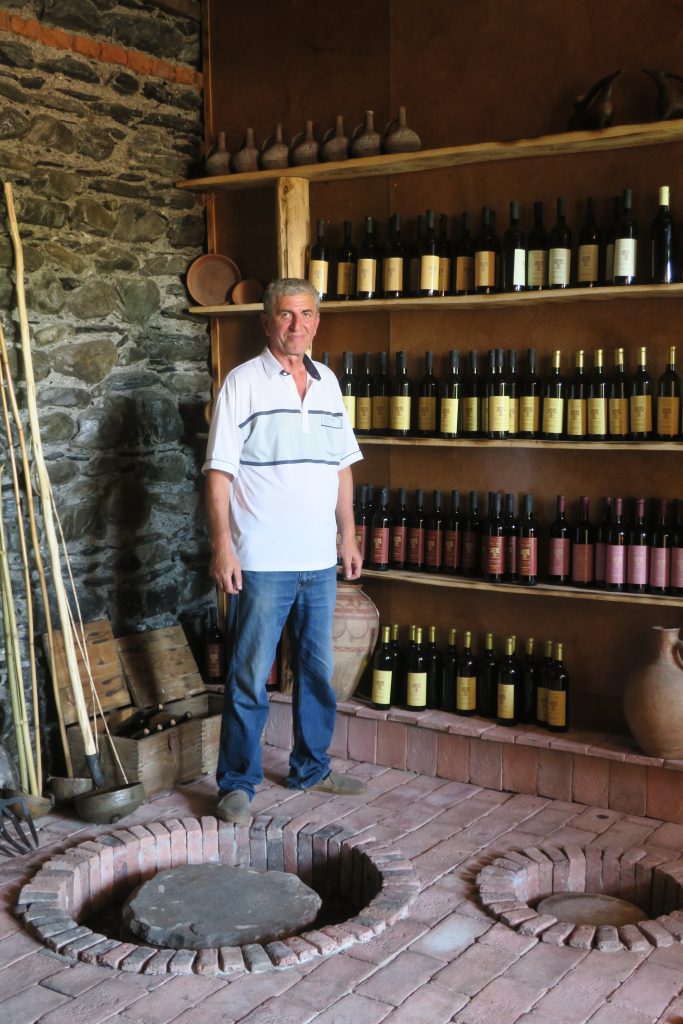

My first of such lunches was, in fact, at a winery: the Old Vine Family Cellar in Kvareli. We arrived not 15 minutes after NaNa’s phone call to the aptly named winery, which was an extension of a family’s home, built alongside a patio shaded by a century-old grapevine. The small winery had several qvevri in the floor. Qvevri — amphora-like clay pots lined with beeswax and buried in the ground — are the cornerstone of traditional Georgian winemaking. Rather than pressing juice into the qvevri, winemakers usually put gently crushed whole grapes inside, including seeds, skins and sometimes stems. As as result, white wines fermented in qvevri can be as tannic as reds. A white Kisi I tried in Tbilisi tasted like a mouthful of fruity burlap.

Giorgi, the owner and winemaker, met us and took us to his cozy tasting room. As a gentleman of a certain age, Giorgi knew more Russian than English, but [insert standard passage about the language of wine being universal here]. And NaNa helped translate the more complicated ideas we wanted to express to each other.

I asked for a spit bucket, which confused NaNa a bit. “So he doesn’t get drunk,” Giorgi explained, though NaNa was clearly skeptical. Georgians don’t seem to worry too much about getting drunk. One of my later guides told me how, the night before, he drank about three liters of wine, he injured his finger, and his friend had somehow broken a rib. Wine is a health food in Georgia, the occasional broken bone aside, and Georgians drink it as such. Toss those kale juicing machines! A qvevri is all you need.

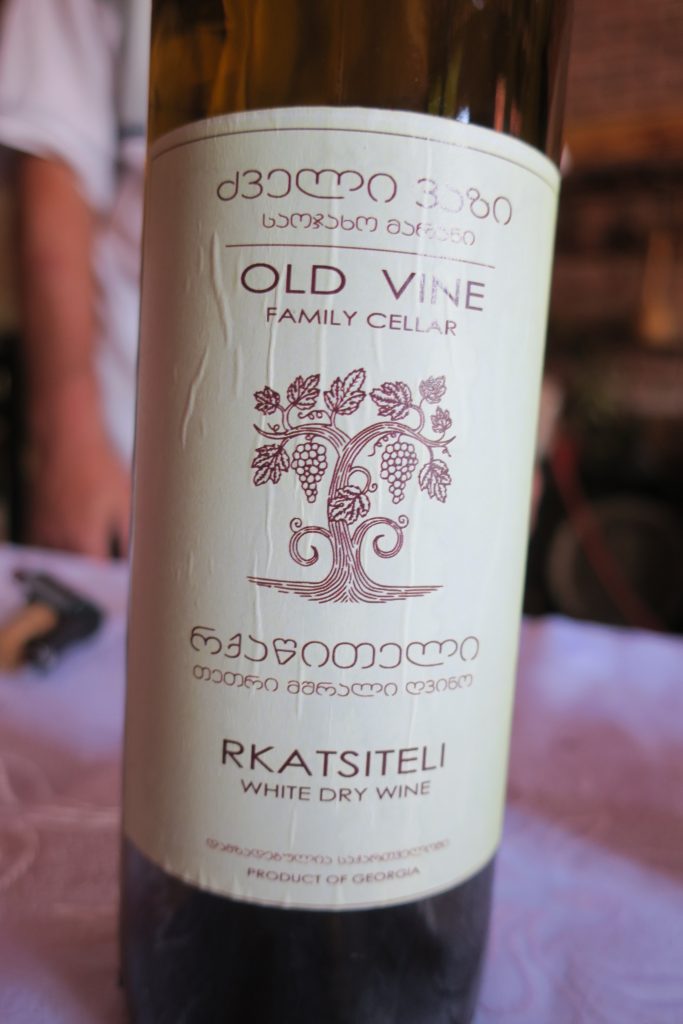

Giorgi’s small, home-based winery doesn’t appear on any list of Georgia’s best, but I’ll be damned if Old Vine Family Cellar doesn’t make some captivating stuff. The Rkatsiteli — one of Georgia’s most important white wine grapes — smelled of peach blossoms and felt surprisingly spritzy. He could have put “pétillant naturel” on the label if he’d wanted to. I loved the juicy acids and well-balanced tannins. NaNa joined me in the tasting, but, of course, refrained from any nasty spitting.

The blend of Rkatsiteli and Mtsvane Manavi was fragrant with peaches and apricots, and developed gracefully from peachy fruit to orangey acids to a tannic finish. Excellent. Mtsvane is another of Georgia’s important white wine grapes, and like Rkatsiteli it often has notes of stone fruits, but I find it tends to be spicier and more floral. Qvevri-made Mtsvane is a bit like tannic Gewürztraminer.

An Rkatsiteli fermented without the grape seeds had aromas of apple and peach, leavened with a freshness like strawberry leaf. It, too, was well-balanced, with ample fruit, round acids and pleasantly nutty tannins, softer because of the absence of the seeds in the qvevri.

An Rkatsiteli fermented without the grape seeds had aromas of apple and peach, leavened with a freshness like strawberry leaf. It, too, was well-balanced, with ample fruit, round acids and pleasantly nutty tannins, softer because of the absence of the seeds in the qvevri.

Saperavi, Georgia’s most important red wine grape, has dark skin and dark flesh (most red wine grapes have only dark skin). It makes inky dark wines full of rich fruit and acid, and Giorgi’s example was no exception. It smelled rich and raisiny, and it had plenty of ripe dark fruit flavor. Yet it didn’t feel at all heavy, with bright sour cherry acids and well-integrated tannins keeping it well in balance.

And I loved the Old Vine Family Cellar blend of Aladasturi, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon, redolent of currants, black pepper and earth. Again, zesty acids kept the wine light on its feet in spite of its rich fruit.

There was nothing amateurish or clumsy about these wines. I would be happy to drink any of them, any time.

When Giorgi suggested that we try some homemade brandy and chacha, NaNa exclaimed, “No! No, it’s too much. Too much to drink.” I gestured to the spit bucket and indicated that I would be happy to try some. Once NaNa saw me trying the spirits, she couldn’t resist trying them herself. The brandy tasted strong but pleasantly nutty; the grappa-like chacha developed slowly, allowing me to get used to its alcoholic power; and I also enjoyed the sweet tarragon liqueur, which reminded me of Italian finocchietto.

We moved to the shady patio, sitting down at a table beneath that massive century-old grapevine. While Giorgi had been pouring wine for us in the tasting room, his wife, Liana, had conjured a feast in the kitchen. Soon our table heaved with colorful salads, local cheeses, pork fritters, bean stew and fresh bread. I reached for the garden tomato and basil salad, but NaNa stopped me. “Wait. I will try first and let you know if it is good,” she said with a twinkle in her eye. She did this with each dish, like a taster protecting a king from poison, pronouncing “This is very good” or, less commonly, “This is just OK.” She must be more of a connoisseur than I, because I found everything to be thoroughly delicious. Our table looked like something out of a travel magazine spread.

“Robbie.” NaNa liked to call me Robbie, which I found oddly endearing. “You should go help with the barbecue! That is a man’s job.” NaNa had a great sense of humor but she could be rather sexist, like many people in Georgia. Earlier that day, I had told her about a wine I tried in a Tbilisi bar, the first vintage by the first winemaker to commercially bottle a wine from a grape called Buera. I was excited to be among the first to try wine made from this grape. She replied, “Buera? No, I don’t know it. But let’s ask the driver. He’s a man, so he knows all the Georgian grape varieties.” (There are approximately 500 Georgian grape varieties.) The driver, unsurprisingly, had not heard of Buera. “No, he doesn’t know it. It must be a foreign wine,” she said, and that was the end of it.

Helping with the barbecue did sound like a good idea in any case. I joined our driver, Bakur, by the grill, filled with smoldering grapevine cuttings. We had no common language and only two skewers of pork to worry about, but we had fun fussing with them and taking photos of each other at the grill. NaNa grew bored, however. “Robbie! Robbie!” she called out, sounding rather tipsy. “Don’t leave me alone for so long!” I lingered for a couple of minutes more by the grill, but NaNa grew more insistent. “Robbie! Come drink with me!” We brought the pork over to the table, and it was perfect: simple and fatty, and flavorful from the grapevine smoke.

I raised my glass to Liana and Giorgi who had joined us. Toasts are important in Georgia, and I wanted to make mine count. “I would like to make a toast to Georgia,” I said, “and to your wonderful hospitality. Look at this beautiful feast! What a joy to share it with you, here, in such a lovely place, while drinking such delicious wine. To welcome me so warmly to your home, and at such short notice — I feel very honored. I won’t ever forget this lunch. To new friends, and to Georgia!” I must have been just a little bit tipsy myself, because I had a tear in my eye as I finished.