The Most Unusual Wine Of Gevrey-Chambertin

As we drove along Burgundy’s Route des Grands Crus, each sign we passed sent a shiver of excitement up my spine. Vosne-Romanée… Chambolle-Musigny… Morey-Saint-Denis… And finally Gevrey-Chambertin, our destination. Even to this old goat of a wine blogger, the thought of doing a wine tasting in Gevrey-Chambertin had me tingling with anticipation.

We pulled up to the Domaine Trapet-Rochelandet (which also makes wine under the name Domaine François Trapet), a relatively modest stucco house on the edge of the village with a tractor parked in front. This is a family winery, and the son, Laurent greeted us at the door. When you picture the scion of a winemaking family located in one of France’s greatest wine towns, you might imagine some sort of grandee in a flawlessly tailored sport coat and trousers and name-brand loafers. But here, in unpretentious and informal Burgundy, Laurent wore a blue athletic shirt, red shorts and hiking boots. He had been working in the vineyards.

The cellar served as both a functional winery and a tasting room, though it clearly was much more the former than the latter. Laurent led us through a fascinating vertical tasting of Trapet’s Le Carougeots, from a village-class vineyard kitty-corner to the La Perrière Premier Cru vineyard and just south of the village itself. We started with a taste right from the barrel.

The 2015 Le Carougeots tasted “noisy,” as Laurent remarked, with youthful acids that still felt a touch overpowering, but this was not at all a bad sign at this point in its life. There was plenty of ripe fruit, too, and I have no doubt the wine will be delicious by the time it’s released. The 2012 had wonderful dark fruit, gentle spice and velvety tannins on the finish, but it was the 2008 that really seduced me, with its sumptuous aroma and flavor of cassis (currant), a note of violets and more forceful tannins. Both vintages were difficult, Laurent explained, but both these wines were delicious, as was the 2007, which had an earthier, more savory character along with stronger spice. Tasting these wines together made it perfectly clear why vintages in Burgundy are so important — each wine had its own distinct character.

Laurent also poured us a taste of the 2013 Les Champs-Chenys, the first vintage of this wine, also made from a single village-class vineyard. Les Champs-Chenys has Grand Cru vineyards bordering it on two sides, which made Laurent think that its fruit might be worth vinifying on its own. He was right. The wine was deliciously complex, with ample dark fruit lifted by notes of fresh hay and vanilla, and after a shaft of white-pepper spice, the finish felt minerally — almost saline.

The two Premier Cru wines we tasted, the 2012 Petite Chapelle and the 2013 Bel-Air, each offered a notable increase in finesse. I loved both — the dark fruit, fresh herbs and peppercorn notes in the Petit Chapelle, and the rich cassis and long finish of the Bel-Air. But I felt truly smitten by the rich Bel-Air, a funny little Premier Cru located just above the hillside from a Grand Cru. Usually Grand Cru vineyards occupy the highest parts of the hills, but because the soil in Bel-Air is so rocky, the vines are “too stressed” to make Grand Cru-level wine, Laurent explained.

The two Premier Cru wines we tasted, the 2012 Petite Chapelle and the 2013 Bel-Air, each offered a notable increase in finesse. I loved both — the dark fruit, fresh herbs and peppercorn notes in the Petit Chapelle, and the rich cassis and long finish of the Bel-Air. But I felt truly smitten by the rich Bel-Air, a funny little Premier Cru located just above the hillside from a Grand Cru. Usually Grand Cru vineyards occupy the highest parts of the hills, but because the soil in Bel-Air is so rocky, the vines are “too stressed” to make Grand Cru-level wine, Laurent explained.

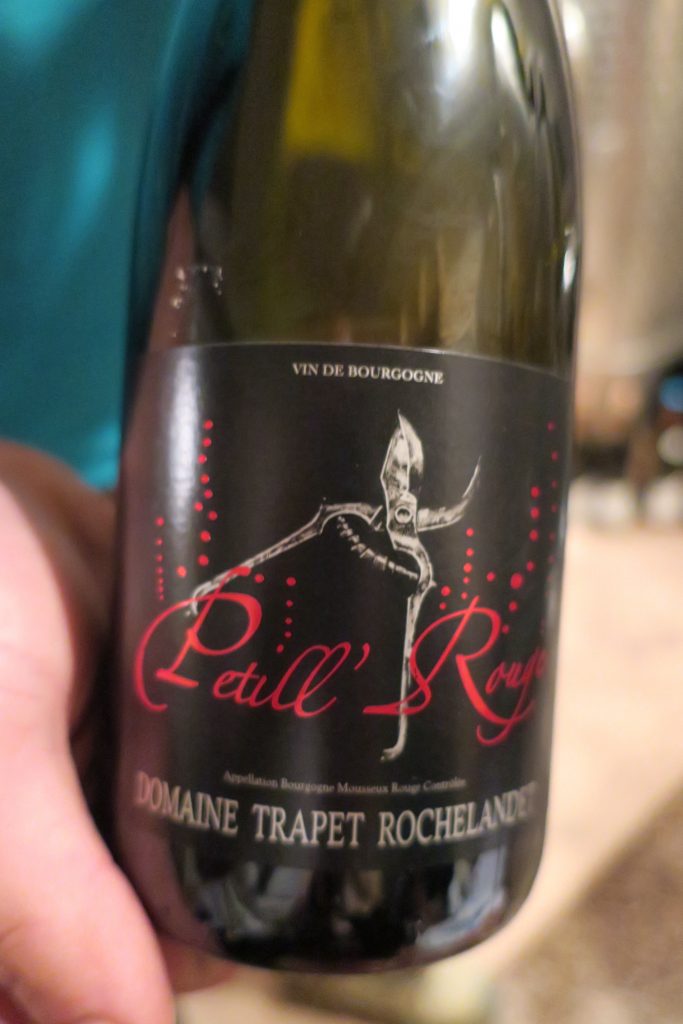

Then Laurent absolutely floored me. He produced a bottle of sparkling wine; a bottle of sparkling red Pinot Noir, in fact. “What?!” My voice went up about a dozen decibels and at least an octave, and it echoed briefly in the cellar. “This is a sparkling red Pinot Noir, made from grapes grown in Gevrey-Chambertin?” I asked, again a little too loudly. I had no idea such a thing existed. Who on earth makes sparkling Gevrey-Chambertin?

Laurent didn’t seem entirely surprised by my reaction. “It is unusual. Actually, this kind of wine was popular in the late 19th century,” he explained, as I listened wide-eyed. He thought it would be interesting to resurrect the style. And indeed, sparkling red Burgundy is officially recognized, as evidenced by the words “Appellation Bourgogne Mousseux Rouge Contrôlée” on the back label. The grapes come from village-class Gevrey-Chambertin vineyards, but because Trapet has no sparkling wine production facilities, a winery in Savigny-lès-Beaune vinifies and bottles it.

The 2014 Petill’ Rouge was most definitely a red sparkling wine, not a Blanc de Noirs, the much better-known bubbly made from Pinot Noir. It looked brick-red in the glass, and it smelled of cherries and earth, as many non-sparkling Pinot Noirs do. The flavor was juicy and earthy, with elegantly small bubbles and some delightfully surprising tannins on the finish. I bought a bottle for about $16 (try finding a Gevrey-Chambertin in your local wine shop at that price).

The 2014 Petill’ Rouge was most definitely a red sparkling wine, not a Blanc de Noirs, the much better-known bubbly made from Pinot Noir. It looked brick-red in the glass, and it smelled of cherries and earth, as many non-sparkling Pinot Noirs do. The flavor was juicy and earthy, with elegantly small bubbles and some delightfully surprising tannins on the finish. I bought a bottle for about $16 (try finding a Gevrey-Chambertin in your local wine shop at that price).

I think of Burgundy’s Côte d’Or as one of the world’s most settled wine regions. For centuries, its terroir has been studied and carefully classified, and at this point its wines, while gorgeous, seemed more or less set in stone. Yet here stood Laurent, pouring me something I’d never even heard of, a wine he wanted to try making just to see how it would turn out.

The Côte d’Or, as I discovered first hand, is not entirely ossified after all. And it won’t become so, as long as winemakers like Laurent continue to take risks and experiment.