Vézelay: Burgundy’s Flyover Country

I regarded the Burgundy map in my World Atlas of Wine with some consternation. In the midst of planning my road trip from Paris to Beaune, I noticed an immense gap between Burgundy’s northernmost vineyards, surrounding Chablis, and its most famous, stretched along the Côte d’Or. The shortest route between my hotels in Chablis and Beaune was 82.6 miles, and the idea of driving that entire length — almost an hour and a half — without stopping for a drink seemed incomprehensible.

Then I noticed it: a little dogbone-shaped speck of pink, hiding in the map’s vast sea of grey flanking the A6 highway. This speck represented Bourgogne Vézelay, which the World Atlas calls a “recondite mini-appellation.” Goodness knows I’m a sucker for a recondite mini-appellation, especially one close to such a lovely (if touristy) town as Vézelay. I planned a detour.

The Oxford Companion to Wine had little to say about the appellation, but my Sotheby’s Wine Encyclopedia was a bit more encouraging, noting that Vézelay’s “top-performing white wines… are superior to the lower end of Chablis, which is relatively much more expensive.” To determine what the top-performing white was, I’m a little embarrassed to admit that I simply googled “best Vézelay winery.”

And it worked! Google suggested Domaine de la Cadette, the wines of which are imported by the legendary Kermit Lynch. Trusting in the judgment of Google and Lynch, I added the winery’s tasting room to my itinerary.

And it worked! Google suggested Domaine de la Cadette, the wines of which are imported by the legendary Kermit Lynch. Trusting in the judgment of Google and Lynch, I added the winery’s tasting room to my itinerary.

The words “Burgundian winery” might conjure visions of grand châteaux, but that’s only occasionally the case in the Côte d’Or, much less in Vézelay. The tasting room looked quite unassuming, in fact, and as I pulled into its parking lot, it also looked quite closed.

Ever hopeful, I walked into the similarly unassuming restaurant, the name of which translates approximately to “The Foot in the Plate” (it sounds ever so much more charming in French). Inside Le Pied dans le Plat, I met the delightful and thankfully English-speaking Martine, who explained that the tasting room had indeed permanently closed. However, the restaurant and winery were affiliated, and I asked if I could do a tasting for my blog. Martine was happy to oblige.

I settled into a shady table on the restaurant’s terrace, decorated with potted succulents interspersed with old green demijohns. A young waitress sat nearby, brushing the dirt from a gorgeous pile of golden chanterelle mushrooms. Martine appeared with the first bottles, and I poured myself a bit of the Melon.

I settled into a shady table on the restaurant’s terrace, decorated with potted succulents interspersed with old green demijohns. A young waitress sat nearby, brushing the dirt from a gorgeous pile of golden chanterelle mushrooms. Martine appeared with the first bottles, and I poured myself a bit of the Melon.

Melon de Bourgogne, in spite of its name, has little presence in Burgundy nowadays, long ago supplanted by Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. This crossing of Pinot Noir and Gouais Blanc now grows more commonly in the Loire. As The Oxford Companion to Wine explains, “Melon’s increasing importance today rests solely on Muscadet, although it is also grown to a limited extent in Vézelay…”

The Melon vineyards in Vézelay may not be as important in the grand scheme of things, but the wine they make can certainly be delicious. The 2014 La Soeur Cadette Melon had an appealingly minerally aroma and zesty flavor, with tart green-apple fruit, lively limey acids and some minerals on the finish.

I also tried two cheerful Chardonnays, the 2014 Domaine de la Cadette “La Châtelaine” and the 2014 Domaine Montanet-Thoden “Galerne” (Valentin Montanet of Domaine Montanet-Thoden is the son of Jean and Catherine Montanet, founders of Domaine de la Cadette, and the wineries are intimately linked). The organic “La Châtelaine” had fresh, creamy fruit leavened with bright, lingering spice — a wonderful contrast. But I liked the “Galerne,” named for a local wind, even better. It had a rounder aroma, more subtle flavors and a more complex journey: the creamy fruit started taut, unwinding and opening into gentle lemon-lime citrus and some light ginger spice.

I also tried two cheerful Chardonnays, the 2014 Domaine de la Cadette “La Châtelaine” and the 2014 Domaine Montanet-Thoden “Galerne” (Valentin Montanet of Domaine Montanet-Thoden is the son of Jean and Catherine Montanet, founders of Domaine de la Cadette, and the wineries are intimately linked). The organic “La Châtelaine” had fresh, creamy fruit leavened with bright, lingering spice — a wonderful contrast. But I liked the “Galerne,” named for a local wind, even better. It had a rounder aroma, more subtle flavors and a more complex journey: the creamy fruit started taut, unwinding and opening into gentle lemon-lime citrus and some light ginger spice.

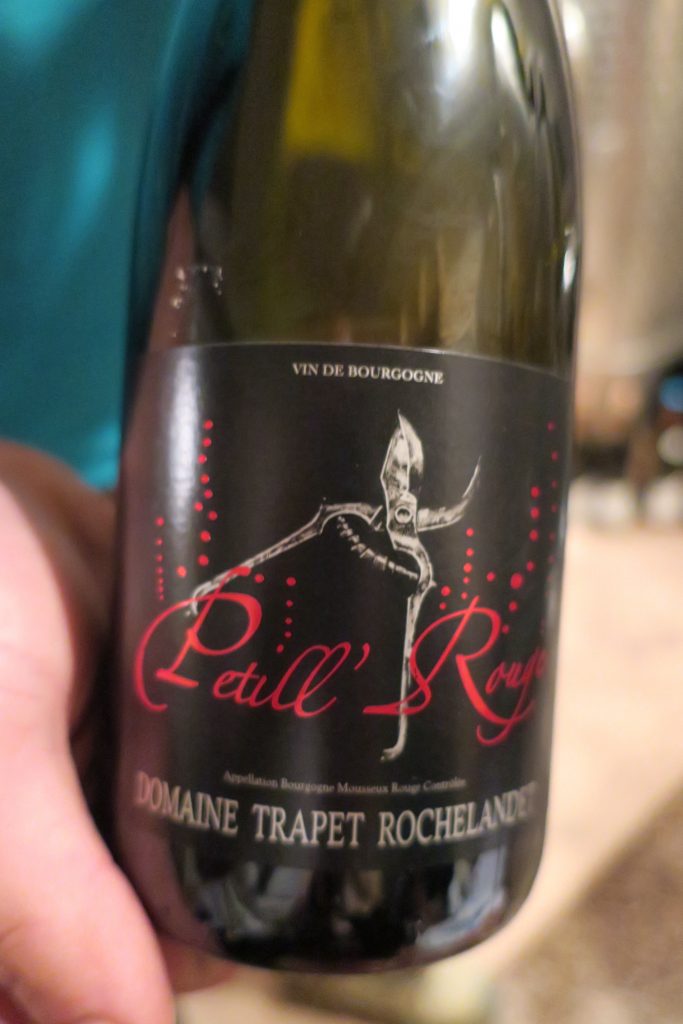

I also tried two charming Pinot Noirs. The 2014 Domaine de la Cadette “Champs Cadet” tasted light and fruity, with a pop of spice. It wasn’t especially deep or complicated, but there’s nothing wrong with a wine that’s simply lively and fun. The 2012 Domaine Montanet-Thoden “Garance” was more serious, with an unusual pink-aspirin aroma and a less fruity character. It tasted more earthy and meaty, with darker, brooding fruit and subtler spice.

Feeling quite comfortable by now at my little table on the terrace, I ordered some trout meunière for lunch. The fish had perfectly crispy skin and delicate flesh, and luscious butter soaked the potatoes and fresh vegetables. Martine tentatively asked me how it tasted. She looked relieved to hear my praise, and said, “Some people complain about all the butter.”

“That’s insane,” I replied. Ordering trout meunière and complaining about the butter is like ordering steak tartare and complaining that your beef is undercooked.

“That’s insane,” I replied. Ordering trout meunière and complaining about the butter is like ordering steak tartare and complaining that your beef is undercooked.

The tight and citrusy “Galerne” Chardonnay was a perfect foil for the trout, cutting right through the buttery richness. I’d had more elegant wines in Chablis, and I would soon indulge in much fancier food in Beaune, but at that moment, with that trout and that Chardonnay, I didn’t want to be anywhere other than the sunny terrace of The Foot in the Plate.

Burgundy has other “recondite” appellations, and one of my favorites is St. Bris, which produces delicious Sauvignon Blanc. To learn more about St. Bris and how I made a fool of myself in Whole Foods, click here.