To Tannat, Or Not To Tannat?

Sorry, Uruguay, to beat up on your signature grape, but I’ve never been very fond of Tannat. The handful of 100% Tannat varietal wines I tried over the years invariably disappointed, with tough and woolly tannins which other flavors and textures in the wine failed to balance. Now, to be fair, the only Tannats I tried in years past cost $10 or less, which means I’d most likely never sampled a Tannat of serious quality. I looked forward, therefore, to the Wines of Uruguay tasting at this year’s Wine Blogger Conference. Would these Tannats — surely some of the country’s best — change my mind? I felt skeptical.

Sorry, Uruguay, to beat up on your signature grape, but I’ve never been very fond of Tannat. The handful of 100% Tannat varietal wines I tried over the years invariably disappointed, with tough and woolly tannins which other flavors and textures in the wine failed to balance. Now, to be fair, the only Tannats I tried in years past cost $10 or less, which means I’d most likely never sampled a Tannat of serious quality. I looked forward, therefore, to the Wines of Uruguay tasting at this year’s Wine Blogger Conference. Would these Tannats — surely some of the country’s best — change my mind? I felt skeptical.

The Oxford Companion to Wine seems to be of two minds about Tannat. It calls Madiran (a wine of southwestern France) “Tannat’s noblest manifestation,” but later goes on to say that Tannat “seems to thrive better in the warmer climate of its new home in South America than southwest France.” The Companion may hem and haw, but The World Atlas of Wine has no problem being direct, stating that “the Tannat produced in Uruguay is much plumper and more velvety than in its homeland in southwest France, and can often be drunk when only a year or two old — most unlike the prototype Madiran.” (Jancis Robinson wrote/co-wrote both books.)

Unfortunately, “plumper” and “more velvety” are relative terms, and they don’t really help answer the question of whether it’s generally a good idea to buy Uruguayan Tannat or not. My experience with Tannat is still far too meager to offer definitive advice, but I stand behind what I wrote in this blog post about a certain Tannat-based blend: Look for Tannat-based blends. In a blend, Tannat’s tannins are much likelier to be softer and more in balance.

With the additional experience of the Wines of Uruguay tasting, I would lengthen that advice to: Look for Tannat-based blends, or a Tannat varietal from a winery you trust. Which means you need a wine shop you trust, or you can trust this blogger and keep an eye out for one of these:

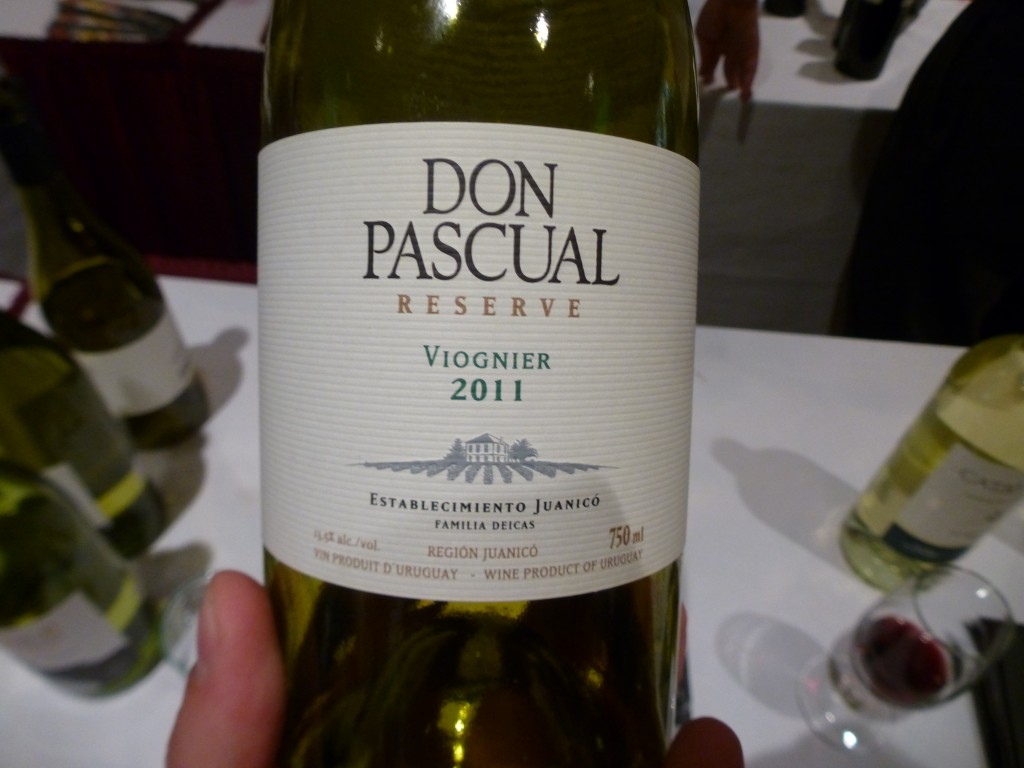

2011 Don Pascual Reserve Shiraz Tannat: Let’s ease into things with a 70% Shiraz/30% Tannat blend. The Don Pascual label falls under the umbrella of Juanicó, which The Sotheby’s Wine Encyclopedia called “One of Uruguay’s fastest-rising wineries.” This blend had an intriguing aroma of vanilla and black pepper, a velvety start on the tongue, a taut midsection and a tart, irony finish. Fruity, bright and pleasantly restrained, this wine was “not overblown, as I must admit I feared,” according to my (decidedly overblown) tasting notes.

2011 Bouza Tannat Reserva: You might have trouble finding this Tannat — it doesn’t even appear on the winery’s website. But if you do run across it, snap it up. I loved the enticing aroma of creamy raspberries, and the rich, up-front fruit on the palate. It grew into some black pepper spice before significant tannins came to the fore, but they weren’t overwhelming. I wrote that this was “as elegant a Tannat as I’ve ever found.”

2011 Giménez Méndez “Identity” Tannat: The “Identity” brand also doesn’t appear on Giménez Méndez’s website, but I would certainly keep an eye out for it. This Tannat sucked me in with its nose of dark, dusky fruit. Also restrained, this wine had a pleasing aromatic quality in the midsection, and serious but perfectly manageable tannins. Another fine Tannat.

2005 Pisano “Etxe Oneko” Licor de Tannat: The Sotheby’s Wine Encyclopedia also speaks highly of the Pisano winery, noting that Eduardo Pisano “has produced some of Uruguay’s best wines in recent years.” If that weren’t exciting enough, I discovered that this particular Licor de Tannat, a fortified wine made in the manner of Port, merited inclusion in The World Atlas of Wine. The original Tannat vines in Uruguay, called “Harriague” by the Basque settlers who brought them, almost all died off over the years. “However,” the Atlas notes, “Gabriel Pisano, a member of the youngest generation of this winemaking family, has developed a liqueur Tannat of rare intensity from surviving old-vine Harriague.” This wine (the name of which means “from the house of a good family” or “the best of the house,” according to Daniel Pisano in the comments below) blew me away with its richly sweet, jammy fruit and impressively balanced acids. These were followed by, as you might expect, a big bang of tannins. Not only is this wine spectacularly delicious, it’s a taste of history. If you see it on your wine store’s shelf, it’s worth the splurge.

Four winners in a row. I got off to a rocky start with Tannat, there is no question, but these wines have me seriously reconsidering. If you like big reds, and you’re in the mood for something a little different, you could do a lot worse than a well-crafted Uruguayan Tannat. And if you like Port, you could hardly do better than Pisano’s Etxe Oneko.

For some more about Uruguayan wine and reviews of some whites, check out this post.