A Revolution In Israel: Fine Wine In The Holy Land

At present, Israel may well be the most misunderstood country in the wine world. What comes to mind when you hear the words “Israeli wine”? All too many of us still think of syrupy-sweet Ruby Port-like bottlings that people sip at Passover, and studiously ignore for the rest of the year.

And yet, Israel “lays claim to being the cradle of the world’s wine industry,” according to The Oxford Companion to Wine. “The southern Levantine wine industry, beginning c.4000 BC, had matured to such a degree,” the Companion explains, “that by the time of Scorpion I (c.3150 BC), one of the first rulers of a united Egypt, his tomb at Abydos was stocked with some 4,500 liters of wine imported from southern Canaan.”

Wine production in Israel continued for approximately 5,000 years, until AD 636, “when the spread of Islam brought about the destruction of the vineyards,” according to the Oxford Companion. “…[W]ith the exile of the Jews, vine-growing ceased.” It wasn’t until the late 19th century that Israel started to rediscover its wine heritage.

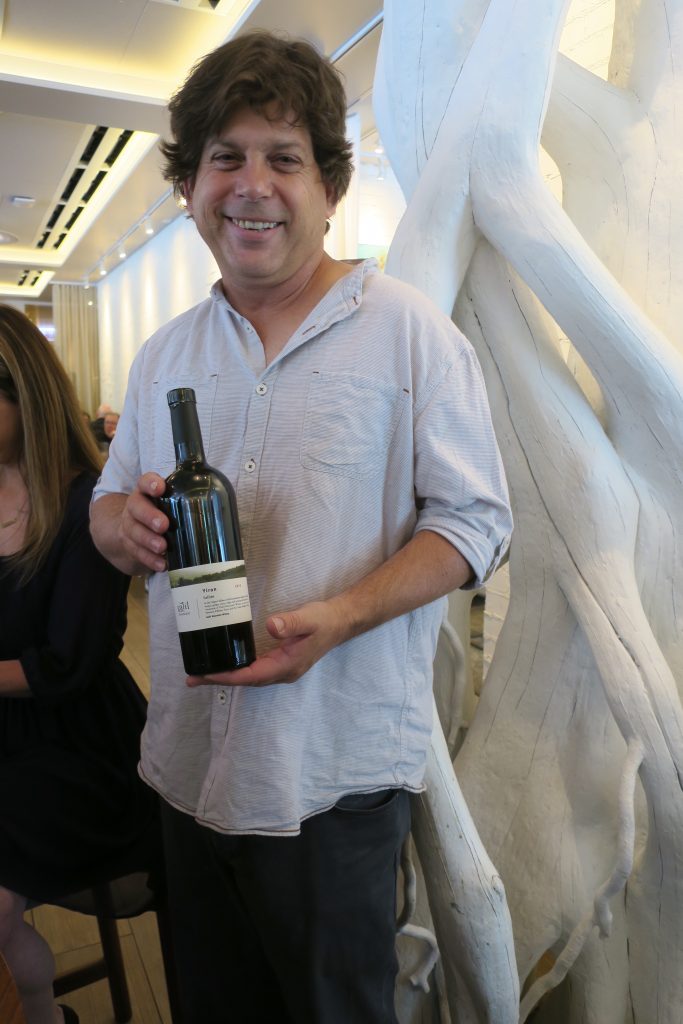

“Israel is an ancient wine region, but we lost all the knowledge because of religious reasons,” winemaker Micha Vaadia of Galil Mountain Winery explained to me at a recent tasting. “But in the last 30 years, we’re reclaiming it.” In recent decades, wineries have reduced production and sought out better vineyard locations, leading them to the higher, cooler elevations of the Golan Heights. Vaadia showed me some photos of his vineyards, lush and green in summer (above) and sometimes blanketed with snow in winter (below).

“In the last 30 years, we learned to make good wine,” Vaadia told me, “and now we’re finding our personality.” Unlike in, say, Greece or Portugal, that personality will be expressed with international grapes. Israel’s indigenous varieties were destroyed about 1,400 years ago. I expressed dismay when Vaadia reminded me of this fact, but he shrugged. “People like to look at the world with international boundaries,” he said, “but biology doesn’t work like that.”

It’s become a defense mechanism, I suspect, for Vaadia to ignore international boundaries. His vineyards stand in the far north of Israel, a tough neighborhood a few miles from both the Syrian and Lebanese borders. I overheard another taster ask him if he’s encountered any problems because of that location. “I live in denial,” he replied.

Vaadia has worked in highly regarded wineries all over the world, including at Jordan in Sonoma, Cloudy Bay in New Zealand and Catena Zapata in Argentina. He returned to Israel and helped Galil Mountain branch off from Golan Heights Winery, one of the first wineries in Israel to win international acclaim, according to the Oxford Companion. Galil Mountain separated in order to better focus on different terroirs, and Vaadia has helped make the winery truly world-class.

I tried nine of his wines, and there wasn’t a single one I didn’t enjoy. A far cry from cloying Manischewitz, these wines all had ripe fruit balanced with freshness and liveliness. They were never ponderous or heavy. I would buy any of the following with my own money:

2016 Galil Sauvignon Blanc: The aroma was big and citrusy, and the wine was no grass bomb. It had taut fruit, pointy limey citrus and a finish which moved from juicy to slightly chalky. Notably sharp focus. I found this wine on sale for $13, which is a downright steal.

2016 Galil Sauvignon Blanc: The aroma was big and citrusy, and the wine was no grass bomb. It had taut fruit, pointy limey citrus and a finish which moved from juicy to slightly chalky. Notably sharp focus. I found this wine on sale for $13, which is a downright steal.

2016 Galil Mountain Rosé: Vaadia poured a taste for me and said, “Lately a lot of rosés are like white wines; this rosé keeps the memory of it being red.” An unusual blend of Sangiovese, Grenache, Pinot Noir and Barbera, the wine had a beautifully shiny, deep pink color. It smelled of fresh strawberry, chalk and orange, and it tasted of watermelon candy. Slow-moving tart citrus kept things balanced, and the wine sharpened up into a dry and surprisingly long-lasting finish. This is a rosé that’s serious at heart but knows how to have fun. For $14 a bottle, it’s another excellent value.

2016 Galil Mountain Merlot: The wine smelled of dark plummy fruit and a little vanilla, but it felt incredibly zesty on the tongue. Fresh and ripe dark fruit gave way to bright acids, black pepper spice and very soft tannins. I found it for $11 a bottle, marked down from $14. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a Merlot of similar quality for that price.

Appetizers at Ema in Chicago

2015 Galil Pinot Noir: When I heard a rumor that Vaadia is seriously considering discontinuing the Pinot Noir, I nearly choked on my hummus. His Pinot has a big, lovely aroma of cherries leavened with a bit of earth, and it had a wonderful zing on the tongue, with big and taut cherry fruit, broad and juicy acids and refined black pepper spice. “Compulsively drinkable” is a wine-writing cliché, and I don’t like to use it except when I really mean it. I really mean it. And it’s a real value for $19 a bottle. Oregon and Burgundy sell Pinots of similar quality for twice the price.

2015 Galil Mountain Syrah: This wine had an enticingly rich, dark aroma with some raspberry and blackberry jam, as well as a touch of vanilla and something savory underneath. It tasted rich and ripe, but again, the wine was strikingly light on its feet. Lively and focused acids balanced the cool and clear dark fruit. The spice slowly expanded in power before evaporating, leaving a crisp finish. What a pairing this would be with some kofta or falafel! The 2014 Syrah can be had for $11, marked down from $15. That. Price. Is. Insane.

2016 Galil Mountain Cabernet Sauvignon: No monster Napa Cab, this. It smelled of dark fruit, mint and vanilla, and through there was plenty of big fruit on the palate, sharp acids and white pepper spice made the wine feel quite bright and fresh. Nor was it tannic; the finish felt surprisingly soft. Very approachable, and a very fine value for $16 a bottle.

2014 Galil “Ela”: I can’t recall ever tasting a blend of Barbera, Syrah, Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc, a mix of Italian, Rhône and Bordeaux grapes, respectively. But it certainly works in this case. The blackberry jam aroma had a note of oak in it, the first time I’d detected any woodsiness in Galil’s wines. It tasted gorgeously ripe, almost jammy, but focused acids and spice more than balanced out the fruit, as did a lift of eucalyptus-like freshness. Some wood on the end felt rather luxurious. The price is higher at $22 a bottle, but even so, it’s worth every penny and then some.

2014 Galil “Ela”: I can’t recall ever tasting a blend of Barbera, Syrah, Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc, a mix of Italian, Rhône and Bordeaux grapes, respectively. But it certainly works in this case. The blackberry jam aroma had a note of oak in it, the first time I’d detected any woodsiness in Galil’s wines. It tasted gorgeously ripe, almost jammy, but focused acids and spice more than balanced out the fruit, as did a lift of eucalyptus-like freshness. Some wood on the end felt rather luxurious. The price is higher at $22 a bottle, but even so, it’s worth every penny and then some.

2013 Galil “Alon”: My favorite wine of the tasting, the “Alon” blends Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc. It smelled of dark fruit with a savory undertone, as well as something fresh. There was that wonderful combination of ripe dark fruit and bright acids again, and in this case, the acids and refined spice developed with slow, even confidence. The tannins on the finish, too, felt supple and elegant. This wine is one classy customer, and it’s an astonishing value at $20 a bottle.

2013 Galil “Yiron”: A blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah, the “Yiron” is one of Galil’s flagship wines. It had a rich aroma of dark chocolate-covered cherries and vanilla, and it felt lush and forceful on the tongue, with ripe, jammy fruit, ample acids and a rather sudden pow of tannins. All the parts are there, but the wine still feels young. In a couple of years it will surely taste more integrated, and I’ll be very curious to try it then. It’s not inexpensive at $32 a bottle, but even so, the wine seems underpriced.

When I mentioned the elegance of the “Alon” to Vaadia, he smiled and said, “Our seasons are so intense. The name of the game is taming the beast. It’s a lot of work introducing finesse.”

These wines hearken back to a winemaking tradition some 5,000 years old, a tradition that was obliterated thanks to a misguided religious edict. Now, Israeli winemakers like Vaadia have rebuilt that tradition from next to nothing, crafting wines of real interest and character. Israel is experiencing nothing short of a wine revolution, and it’s a great story.

But more important for the wine consumer is the excellent quality-to-price ratio. Because Israel’s reputation hasn’t caught up with the quality of its wines, bottlings like the ones above sell for far less than comparable examples from more famous wine regions. My wine rack can expect to see a regular rotation of Galil from now on.