When To Decant, When To Aerate, And When To Just Back Off

Dinner last week at my parents’ house got me thinking about decanting. I brought a 2009 Brunello di Montalcino, to pair with the beef tenderloin my father was whipping up. We opened it and poured ourselves small tastes, not only because of the wine’s youth (seven years, while old for most wines, is fairly young for a Brunello), but because wine streaked the cork from top to bottom. Air might have come into contact with the wine, oxidizing it.

Fortunately, the wine remained intact, but the tannins still felt tough and the fruit tasted tightly wound. Because we planned on eating in about 15 minutes, I decided it was time to decant. Or, more accurately, since my parents don’t own a decanter, we decided it was time to attach a little plastic nozzle to the bottle which helped aerate the wine as it was poured.

The wine unwound a little faster than it would have just standing in the bottle, and it ended up pairing beautifully with the beef in mushroom gravy. The ample but taut red fruit combined with lively spice and somewhat softened tannins to clear the palate after each rich, beefy bite.

I follow this procedure — tasting a little bit first — with any wine that I suspect might still be in the throes of youth. There is no other way to determine whether a wine needs to be decanted or not. You may very well find other wine writers who tell you that such-and-such wine always needs to be decanted, but don’t believe them. Even if they have an authoritative-sounding book.

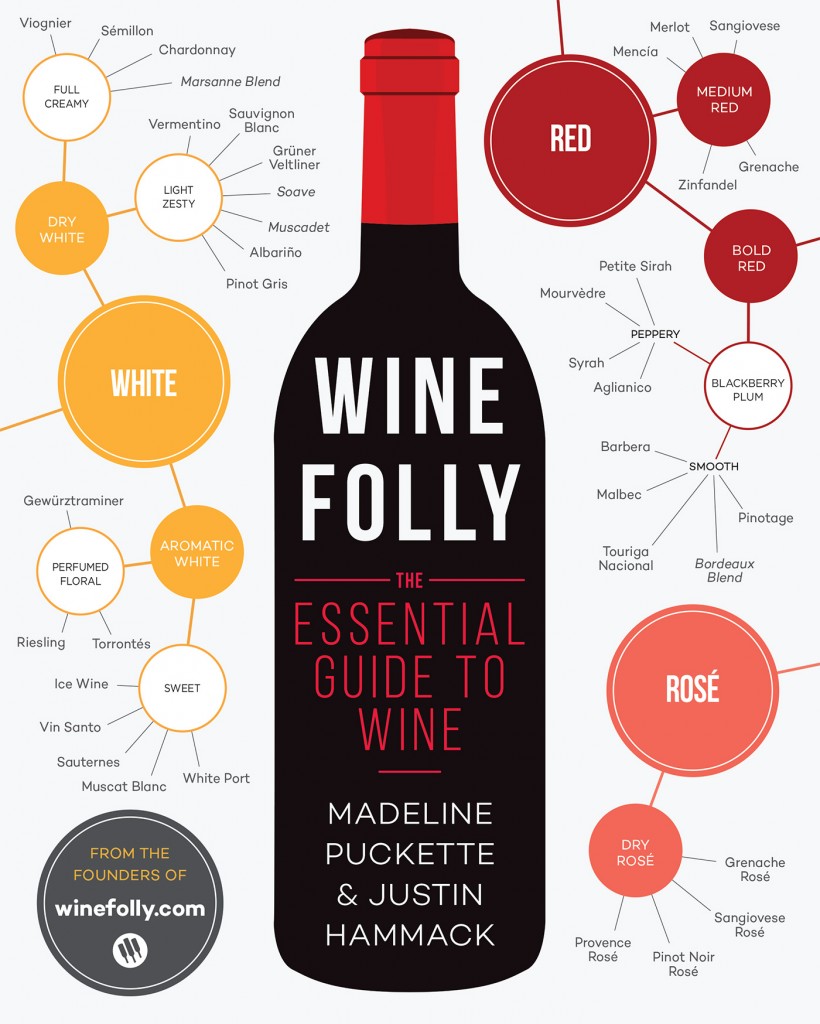

Last year, for example, when I reviewed the otherwise commendable book “Wine Folly” by Madeline Puckette and Justin Hammack, I discovered, in large font and all capital letters at the top of page 27, the title, “AERATING WINE TO IMPROVE FLAVOR.” The introductory paragraph described decanting as “magic,” and farther down the page, there was this criminally misleading assertion: “All red wines can be aerated.”

Last year, for example, when I reviewed the otherwise commendable book “Wine Folly” by Madeline Puckette and Justin Hammack, I discovered, in large font and all capital letters at the top of page 27, the title, “AERATING WINE TO IMPROVE FLAVOR.” The introductory paragraph described decanting as “magic,” and farther down the page, there was this criminally misleading assertion: “All red wines can be aerated.”

This is nothing short of absolute nonsense. Decanting an old wine is the vinous equivalent of asphyxiating your grandmother with a pillow. I still smart at the memory of a foolish waiter at a Chicago BYOB restaurant breaking the cork on a 1986 Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon, pushing the remaining cork piece into the bottle, and then decanting it through a coffee filter. When I saw what he was doing at the waiter station, I stopped him in his tracks, but the damage to the half of the wine he decanted was done. It fell flat, lacking the liveliness of the portion remaining in the bottle.

But it’s not just old wines that will suffer from decanting. Try decanting this year’s Beaujolais Nouveau, and you’ll get an even nastier surprise than usual when you taste it. In the unlikely event that it had some structure in the first place, you’ll have aerated it into oblivion. You also won’t do yourself any favors by decanting an expensive but delicate Pinot Noir, nor that unoaked red that precisely maintains its balance.

Taste first. If the wine tastes unpleasantly tight — if it makes you pucker a bit and/or the tannins rasp the buds right off your tongue — decant if you’re in a hurry, or simply let it stand open a bit. If you automatically decant, you’ll miss how the wine develops and changes in the glass over time, and that’s one of wine’s great joys.

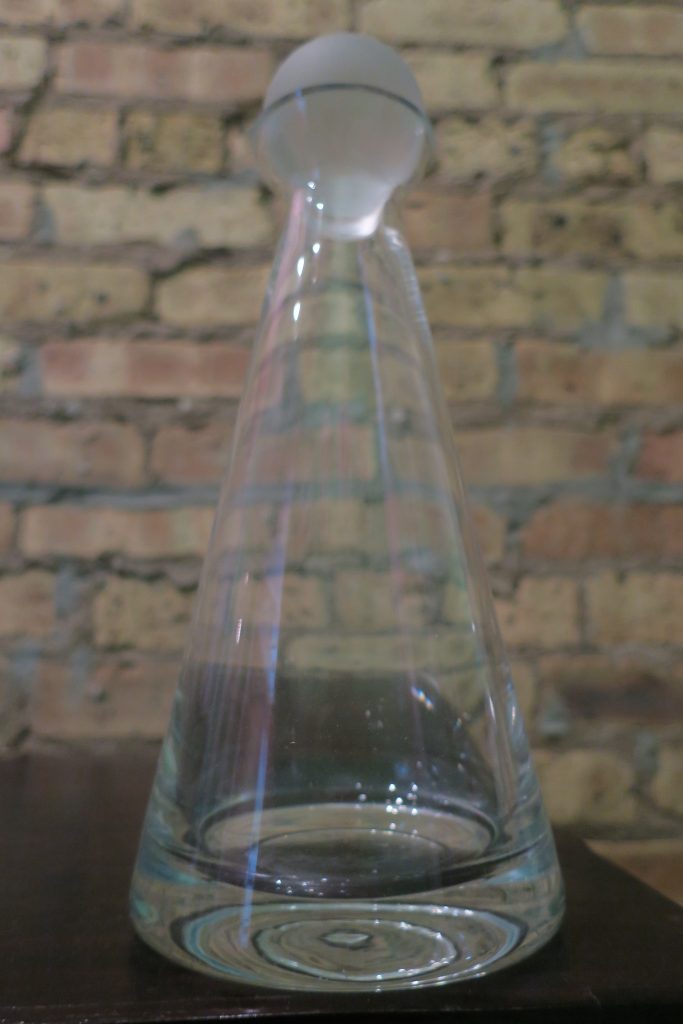

The decant-first-ask-questions-later philosophy is so insidious that entire companies have devoted themselves to finding ways to introduce ever more oxygen into your wine, as I discovered at this year’s Wine Bloggers Conference in Lodi, California. The latest aeration contraption, demonstrated for us at the conference, is called Velv™.

The decant-first-ask-questions-later philosophy is so insidious that entire companies have devoted themselves to finding ways to introduce ever more oxygen into your wine, as I discovered at this year’s Wine Bloggers Conference in Lodi, California. The latest aeration contraption, demonstrated for us at the conference, is called Velv™.

(Full disclosure: Velv™ sponsored a lunch for conference attendees.)

As the Velv™ website describes, “Unlike decanting and aeration methods that rely on ambient air, Velv™ Wine Oxygenator uses 99.5% pure oxygen to bring wine to its flavor peak in just minutes.”

It’s not actually air that changes a wine’s flavor profile. Oxygen, specifically, is what causes the chemical reaction in the wine. But air is only 20.95% oxygen, which suddenly makes a decanter seem wildly inefficient compared with the pure and ruthless Velv™.

This wand-shaped device has a canister of oxygen in the handle, and at the tip, a “micro-diffuser” that you stab into your glass or bottle of wine. The machine forces tiny bubbles through the diffuser, ensuring that the wine has maximum contact with the oxygen.

I observed the Velv™ in action at the conference, and as I watched, I heard the sales representative say the most remarkable thing to one of my fellow bloggers: “After six minutes, [the Velv™] took all the gravel and the dirt and the ugliness out of a Bordeaux.” I stood there, mouth agape, as I transcribed the conversation in my notebook. I wonder what that Bordeaux winemaker would think about all that “ugliness” — some might call it character or complexity — being removed from his or her wine.

I later related the conversation to a friend at the conference, who asked, “Why would you want to turn a Bordeaux into a California Merlot?”

California wines, incidentally, did not escape the violent bubbles of the Velv™. The sales representative went on to enthusiastically describe how the machine “…can also blow the oak and butter out of a big Chardonnay.”

Of course, the other way to avoid oak and butter flavors, which some people legitimately dislike, is to purchase an unoaked Chardonnay. Most wine shops carry at least one these days. Then you’ll be able to taste the wine as the winemaker intended it to taste, and you’ll have saved yourself $250 to $300.

The Velv in action, inserted into a Ménage à Trois

Distressing sales pitches aside, the only way for me to determine the effect of the Velv™ was to experience it for myself. The sales representative poured me two tastes of a 2013 Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon, one velved and one not.

He recommended trying the velved version first. It still had lots of dark fruit to it, and more surprisingly, the tannins still dried my tongue right up. I thought they might feel a bit softer after all that oxygen.

Then I tried the non-velved Cabernet. Wow. The fruit was all there and the tannins felt similar, but the wine tasted spicier. The Velv™ had removed that key component of the Cab — the spicy quality in the middle — and with the spice intact, the wine felt more balanced. I much preferred the Mondavi with its midsection not blown to bits with the Velv™ blunderbuss.

In short, should you decant your wine? Probably not. Should you spend $250 on a device to literally gas your wine? In the name of all that’s good and holy, no.

I’m sorry, Velv™ sales representative. I guess I owe you lunch.