What Does A $500 Wine Taste Like?

There is a widespread suspicion that high-end wines are something of a con, even among high-end winemakers themselves. I recall a swanky Bordeaux tasting I attended where I chatted with the owner of a Sauternes winery. He did not mince words about trophy wines: “You know, to be perfectly honest, I never buy wines that cost more than 50 or 60 euro. That’s maybe $100? Anything that costs more than that is bull****. When you buy wines,” he gestured towards the room, “that cost $300 or $800, you are not buying the wine. You are buying the label. I want to buy only the wine.”

Because I have limited experience with wines in the $300-$800 price bracket, and because it suited my own prejudices, I was inclined to believe him. What could you possibly get for $500, say, that you couldn’t in a $250 bottle? Would the $500 wine be twice as good as the $250? And of course, the $250 should theoretically be twice as good as a $125 bottle, which should be twice as good as a $62 bottle, which should be twice as good as a $31 bottle, which should be twice as good as the $15 bottle that I typically have on my rack at home.

Which means that a $500 bottle should, with that kind of quality, literally make my head explode with joyous rapture. Literally. I mean blood-on-the-ceiling joyous rapture explosion.

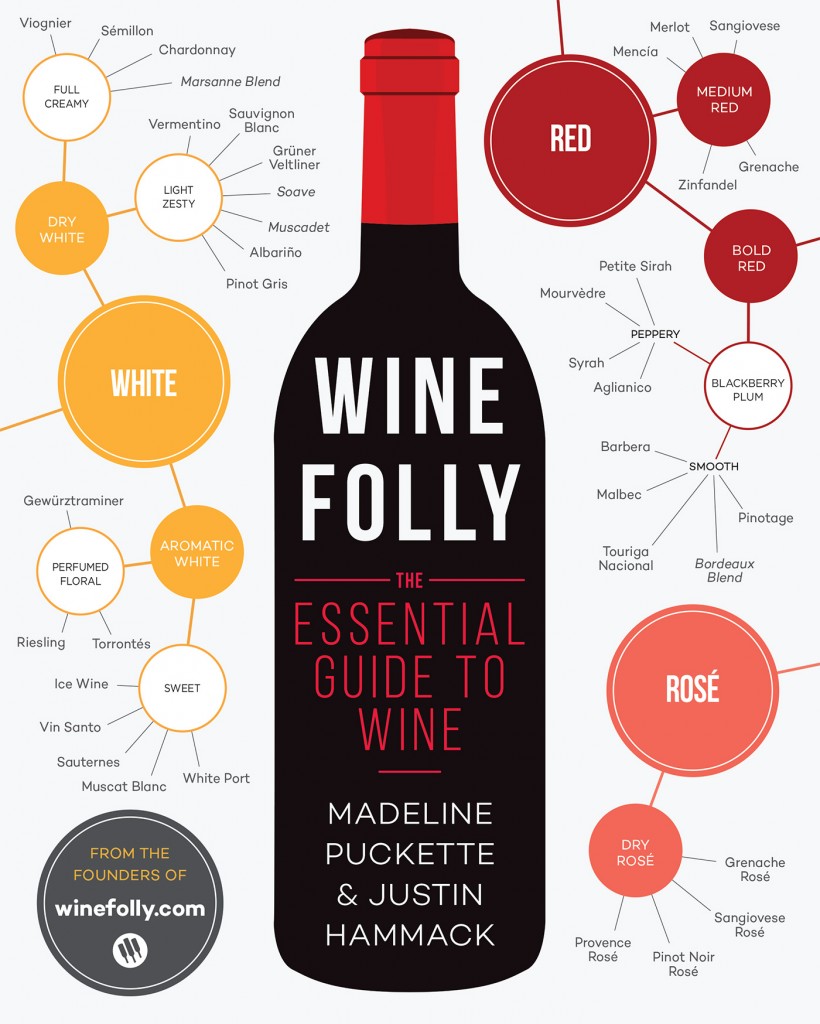

Fortunately for the condition of my head, wine tends to occupy a more logarithmic scale, which means that though there will indeed likely be a gigantic leap in quality from an $8 bottle to a $15 bottle and again from a $15 bottle to a $30 bottle, the returns start to diminish as wines become more expensive. So how could a $500 wine be worth it?

You do get something for all that expense. At a recent tasting in Chicago’s Maple & Ash restaurant, I had the fortune to sample three $500 wines in succession. Well, two $500 wines and one $535 wine. I observed the room during the tasting, and many of the men (the guests were almost exclusively men) did indeed appear to be enraptured. I must admit I felt some shivers of delight myself, as I tried them.

You do get something for all that expense. At a recent tasting in Chicago’s Maple & Ash restaurant, I had the fortune to sample three $500 wines in succession. Well, two $500 wines and one $535 wine. I observed the room during the tasting, and many of the men (the guests were almost exclusively men) did indeed appear to be enraptured. I must admit I felt some shivers of delight myself, as I tried them.

These were wines by Gaja (pronounced guy-a), one of Italy’s most formidable wine families, which has vineyards in Barbaresco, Barolo, Bolgheri and Brunello. But it’s the Barbarescos that fetch top dollar. Or more accurately, the Langhes. As I learned from The Oxford Companion to Wine, which devotes an entire column to Gaja, Angelo Gaja thought that his coveted single-vineyard wines had hurt the reputation of his traditional Barbaresco, which is blended from multiple vineyards. So, as is common in unnecessarily complicated Italy, Gaja now sells its most expensive bottlings under a basic catch-all appellation, Langhe DOC, instead of the ostensibly more prestigious Barbaresco DOCG.

At the tasting, I tried the 2013 Gaja Barbaresco, a blend of 100% Nebbiolo grapes from 14 different vineyards around the town. Barbaresco, incidentally, was for ages not an especially popular wine. “Barbaresco did not enjoy Barolo’s connection with the House of Savoy and the nobility of the royal court in Turin,” The Oxford Companion explains, “and suffered in relative commercial obscurity until the efforts of Giovanni Gaja and Bruno Giacosa in the 1960s demonstrated the full potential of the wine.”

It’s difficult now to imagine that Barbaresco was once the ugly duckling of Piedmont. If anyone has any lingering doubts about Barbaresco’s potential, Gaja’s example will smash them into pomace. I loved the 2013, even in its youth — the dark-red fruit aroma had a savory note underneath, as well as a floral overtone. The wine moved gracefully from ripe fruit to white-pepper spice to supple, dusty tannins. It is an absolutely beautiful wine, with poise and elegance, but its suggested retail price is only $240, and we’re not here to talk about bargain Barbaresco. Let’s move on to the pricey stuff.

But first, why are these wines so pricey, anyway? Gaia Gaja, the fifth generation in her family to work at the winery, presented the wines we tasted, and she provided part of the explanation: Gaja takes great pains to create healthy vineyards, using its own compost, seeding vineyards with a mix of plants from local meadow in order to improve biodiversity, introducing bees, and planting some 250 cypresses to serve as a refuge for small birds, among other measures. “The birds eat grapes,” Gaia Gaja told us, “but they also eat harmful insects, so we have to be generous.”

And, of course, making top-quality wine is expensive and labor-intensive. Gaia Gaja noted that the winery doesn’t hire many seasonal workers, relying more instead on full-time staff. “Seasonal workers know agriculture,” Gaia Gaja explained, “but not Nebbiolo vines.” The winery decided to train people and keep them on staff, ensuring that its workers really got to know the vineyards and how to coax the best fruit from them.

But perhaps the biggest factor in the price is simply that there is limited supply and high demand. Gaja, as evidenced by the family’s numerous appearances in The Oxford Companion, is a wine giant, and when a name has great renown, that name drives up the prices (that’s why I usually write about more obscure wines — they’re what I can afford).

Gaja’s wines, however, are more than just a name — they have the quality to back up their hype. Let’s examine the evidence:

2013 Gaja Sorì Tildìn, suggested retail price, $500: “Sorì” is a local Piemontese word indicating a desirable vineyard. The aroma of dark-red fruit is rich and forward, and that big fruit continues in the taste. This wine is powerful, with immense fruit, lively acids and youthful tannins. Deliberate and slow-building white-pepper spice marked the finish. That slow build was a delightful surprise, and although the wine felt youthful and bold, it moved from flavor to flavor with impressive finesse.

2013 Gaja Sorì San Lorenzo, suggested retail price, $500: This wine was one of the first single-vineyard bottlings of Nebbiolo in the region, first sold in 1967, and as such, it helped put Barbaresco on the map. It had a rather dusky, hooded, dark-red fruit aroma, marked with some spice and some purple flowers. Again, this wine tasted big and brawny, with dark-red fruit flavors quickly moving to white-pepper spice and strong (some might say “tough”) tannins. It needs a little longer to mature, but even now, in its headstrong youth, it exhibits finesse as it shifts gears from fruit to spice to tannins.

Giovanni Gaja, Gaia Gaja and Bill Terlato

2013 Gaja Costa Russi, suggested retail price, $535: “Costa” is the Italian version of côte, or slope. Here the dark-red fruit in the aroma was accompanied by some meaty notes as well as an overlay of violets (as I write this, I realize that combination sounds rather horrifying, but actually it’s thoroughly enticing). This wine had the slowest development of the three. It took its own graceful time to unfold, moving from concentrated fruit to focused acids to sneaky tannins. They started softly at first, and it wasn’t until I was in the thick of them that I realized their power.

What all three wines have in common is great finesse. It might be difficult to imagine, but when you taste a wine that has it, finesse is unmistakable. It’s like riding with an expert driver in a manual-shift car. Anyone who knows how to drive a stick can get you where you’re going, but the journey is ever so much more graceful and enjoyable with an expert maneuvering the gears and clutch.

But are these wines worth it? That depends. Let’s say you make about $50,000 a year, and you think $50 is an affordable splurge on a bottle of wine. To make a similarly affordable splurge on one of the three wines above, you would have to be making $500,000 a year.

If you are indeed one of those high-earners, these wines won’t disappoint. They offer a seductive and life-affirming combination of richness, power, balance and finesse. I loved tasting them. They put me in a brilliant mood for the rest of the day. I practically skipped home.

But would I spend 1% of my yearly earnings to purchase a bottle? I think I’ll have to settle for a ride in which I feel the gear shifts a bit more.