Grappa: Not Just For Breakfast Anymore

Tell people that you’re going to a grappa tasting, and the response will likely be “Ugh.” Go on to say that the tasting is at 9 a.m. over breakfast, and the response will likely be some sort of attempt at an intervention. In my defense, there is, in fact, a long tradition of drinking grappa at breakfast (or at least with espresso), as evidenced by Caffè Corretto, or “Corrected Coffee.”

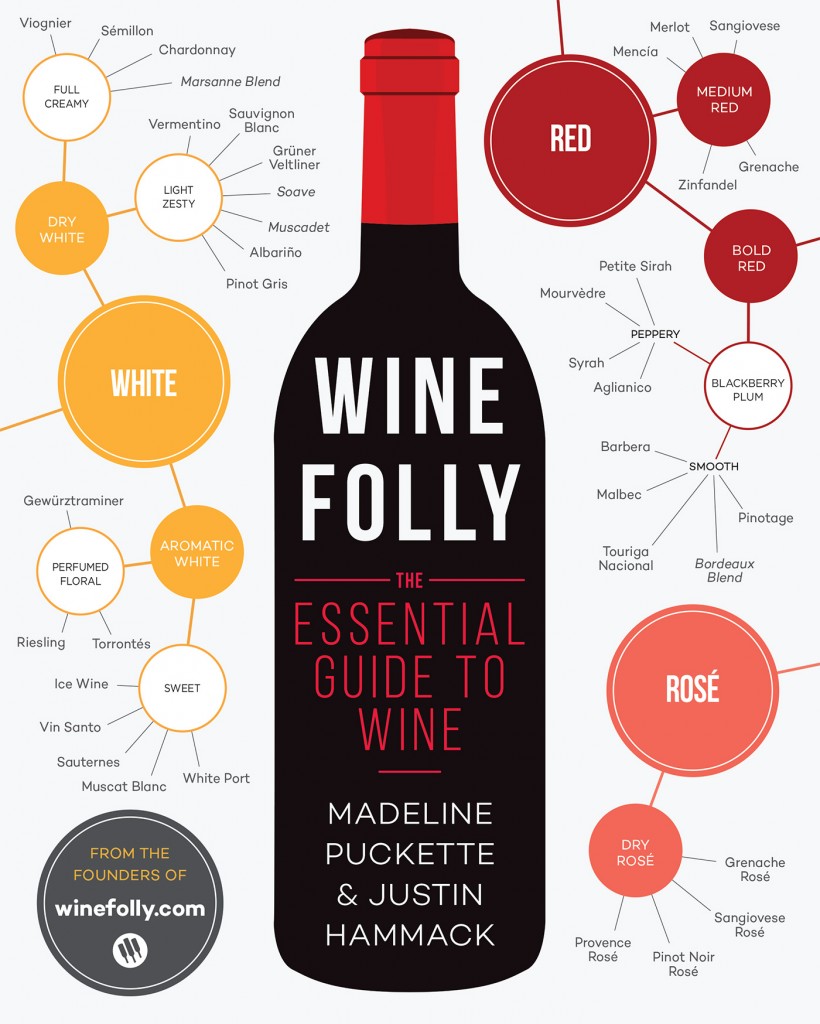

Actually, no one I talked to expressed any concern whatsoever about my tasting spirits at breakfast (I’m not sure if that’s good or bad). But grappa… that concerned everyone. This northern Italian spirit distilled from grape pomace — the stems, seeds, skins and pulp — has a reputation for rusticity, to put it kindly. Indeed, for a long time, it was a spirit of the poor, created from the leftovers of winemaking. A “refined grappa” was an oxymoron.

Actually, no one I talked to expressed any concern whatsoever about my tasting spirits at breakfast (I’m not sure if that’s good or bad). But grappa… that concerned everyone. This northern Italian spirit distilled from grape pomace — the stems, seeds, skins and pulp — has a reputation for rusticity, to put it kindly. Indeed, for a long time, it was a spirit of the poor, created from the leftovers of winemaking. A “refined grappa” was an oxymoron.

I was lucky. The first time I tried grappa was in Venice at a bar just off the Fondamente Nove, about 15 years ago. It was a Grappa di Amarone — even then I knew that Amarone was something special. The bartender approved of my choice, and I still remember its rich raisiny quality mixed with alcoholic fire. I also purchased a slender bottle of delightfully floral Moscato grappa to bring home.

At the time, I didn’t know that varietal grappas were a relatively new creation, invented by the estimable Nonino distillery (traditionally grappas are blends of various grapes). Nonino first distilled a single-varietal grappa in 1967, and it wasn’t until 1973 that the distillery created “the first Cru single varietal Grappa: not by chance this time but as the result of their love for their work, study, research and experimentation,” according to the company’s website.

“We go against the rules for grappa,” Elisabetta Nonino told me over a breakfast of avocado toast. “The rules are very bad. They are all against quality.” Grappa is not Cognac. You really have to choose your producer carefully. And I can’t imagine that there are many producers which take more care with their grappa than Nonino.

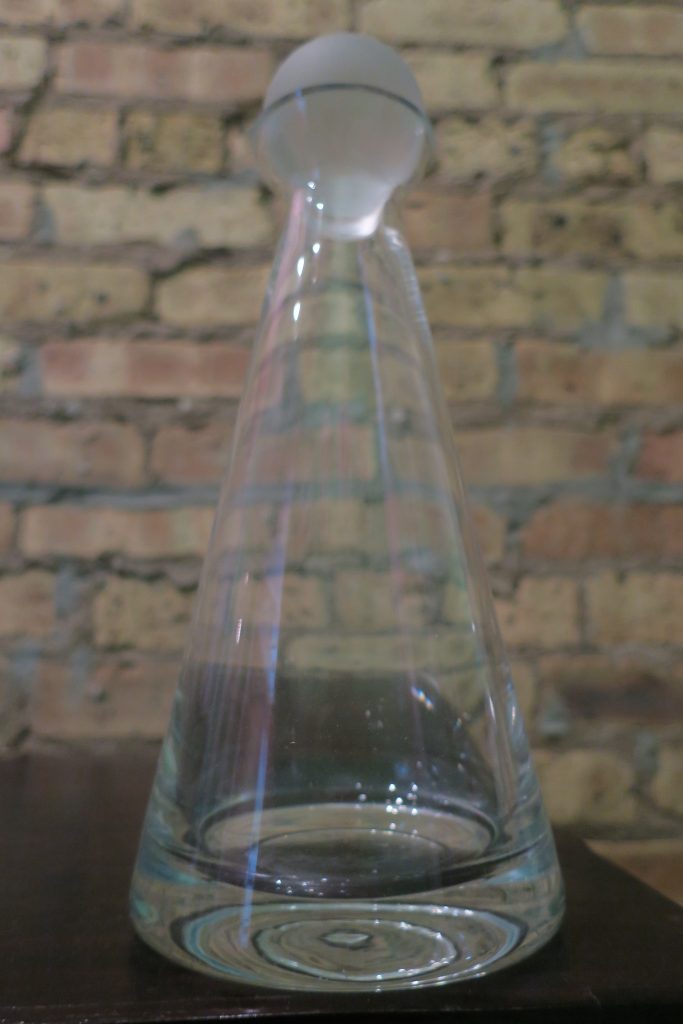

First, there are the stills. The distillery contains no fewer than 66 pot stills (12 for each member of the family, plus one for each niece and nephew, Elisabetta explained). Why so many? Nonino produces numerous single-variety grappas as well as various fruit brandies, and all the fruit is distilled fresh, making a big difference in terms of flavor. That means the stills are in use only nine or 10 weeks each year, during the harvest season, but during that time, each is required.

Second, Nonino removes the grape stems from the pomace, distilling only the pulp, skins and seeds. This extra step adds to the refinement of the grappa.

Elisabetta grew up in the distillery, learning the art of grappa production from observing her family at work. Her parents told her, “First learn to distill, then study whatever you want.” But her heart was always with the family business, even as she studied Political Science at the university. “It took longer than usual to graduate,” Elisabetta said. “‘I can’t take my exams in April,’ I told my professors. ‘No no, that’s Vinitaly!'” If the grappas I tasted are any indication, she made the right choice for her profession.

The traditional Nonino Vendemmia grappa, made from a blend of Prosecco, Malvasia and Pinot Noir, has a fresh, slightly raisiny aroma and ample raisiny flavor. It remains smooth on the tongue for quite some time, delaying the alcoholic power until the last moment. It’s spicy, but classy. I noticed that when I smelled this grappa, it didn’t burn my nostrils at all — nor did any of the others I tried.

Even more interesting was Il Merlot di Nonino grappa, which started with a lush texture and lots of raisiny fruit before moving to clean, alcoholic spice. But I really fell for Il Moscato di Nonino grappa, which brought back memories of that trip to Venice. I loved its aroma, reminiscent of lily of the valley, as well as its slow development on the palate. It moved gracefully from smooth and perfumed to powerful and spicy. It cut right through the fat of my pork belly eggs Benedict.

On Elisabetta’s recommendation, I tried making some cocktails with the Moscato grappa later at home. You can find plenty of interesting grappa cocktail recipes on the Nonino site, but in order to really let the grappa come to the fore, I wanted as simple a cocktail as possible. First I tried the Moscato grappa with some fresh lime, but I preferred the roundness of fresh lemon juice. Two parts Moscato grappa, one part fresh lemon and a healthy dash of simple syrup (or a couple of teaspoons of sugar) makes for an exceedingly delicious drink: round, citrusy and just a touch floral, with a pleasantly raisiny aftertaste.

On Elisabetta’s recommendation, I tried making some cocktails with the Moscato grappa later at home. You can find plenty of interesting grappa cocktail recipes on the Nonino site, but in order to really let the grappa come to the fore, I wanted as simple a cocktail as possible. First I tried the Moscato grappa with some fresh lime, but I preferred the roundness of fresh lemon juice. Two parts Moscato grappa, one part fresh lemon and a healthy dash of simple syrup (or a couple of teaspoons of sugar) makes for an exceedingly delicious drink: round, citrusy and just a touch floral, with a pleasantly raisiny aftertaste.

I also sampled some barrel-aged grappas, akin to French Marc. The Noninos take no shortcuts here, either, keeping their aging cellars under lock and key, controlled by a government official who records each entry into the facility. When the Noninos tell you that your grappa was aged, say, a minimum of three years, there is no question that it was. The distillery has documentation to prove the fact.

Aged one year in barriques, Il Chardonnay di Nonino grappa had the classic raisiny aroma, but there was a vanilla note in there, too. It tasted rich and balanced, starting almost sweet, with a touch of cream and a bit of wood, moving to a spicy build-up followed by a freshly herbaceous finish. What a delight.

Made from a blend of Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Schioppettino grape pomace, the Riserva grappa is aged between three and 18 years in barriques. Its aroma had more wood to it, underneath notes of dark fruit. After a rich start, a note of fresh tobacco took over followed by a spicy midsection and a lift of green herbs. The finish, marked by notes of wood, vanilla and caramel, seemed to go on and on.

Made from a blend of Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Schioppettino grape pomace, the Riserva grappa is aged between three and 18 years in barriques. Its aroma had more wood to it, underneath notes of dark fruit. After a rich start, a note of fresh tobacco took over followed by a spicy midsection and a lift of green herbs. The finish, marked by notes of wood, vanilla and caramel, seemed to go on and on.

Italy has a knack for turning food and drink that was originally popular with peasants into something fit for royalty. Nonino’s grappa happily fits right into that tradition. Next time you’re out to eat at a nice restaurant, check the spirits list to see if the bar offers a Nonino grappa. It makes for a surprisingly elegant digestif, and not just at breakfast.

Note: The grappa tastes and my pork belly eggs Benedict were provided free of charge.